Oil for (almost) nothing and gas for free

Natural resource giveaways to friends and family have long been a global concern, and there is an extensive literature documenting the problem. This 1999 paper by the International Monetary Fund, for example, finds a link between the degree to which a nation or state is dependent on natural resources and the level of corruption. This paper from 2009 divides the problems into corruption and patronage:

Resource rents induce rent-seeking as individuals compete for a share of the rents rather than use their time and skills more productively. And resource revenues induce patronage as governments pay off supporters to stay in power, resulting in reduced accountability and an inferior allocation of public funds.

Diversion of extraction rights and payments from natural resource endowments is such a large problem, and so widespread, that a global effort has been made to address it systematically through the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative. By standardizing data and requiring reporting of key information along the value chain of this industry, EITI can make diversion and corruption much more difficult to hide. If it is harder to hide, it happens less often. And less corruption also has benefits for international competition. If all parties know their side payments and special deals will be visible, and no one party can get a competitive advantage this way, the cost structure of the entire industry isn't eroded as it would be in a corrupt system.

Trump administration seeking to strip transparency, pump up lease volume

Despite the benefits of EITI, the Trump Administration withdrew in November of 2017. Bloomberg notes that the US joined Azerbaijan in this regard. It is notable that Azerbaijan is ranked in the bottom third of countries in terms of the Transparency International 2017 corruption perceptions index , with a score of only 31 out of 100.

The American Petroleum Institute, along with some oil majors, fought behind the scenes against the required reporting under EITI. While their polished PR staff have verbally committed to addressing corruption and transparency in other ways, their words are worthless absent required disclosure. They obviously know this.

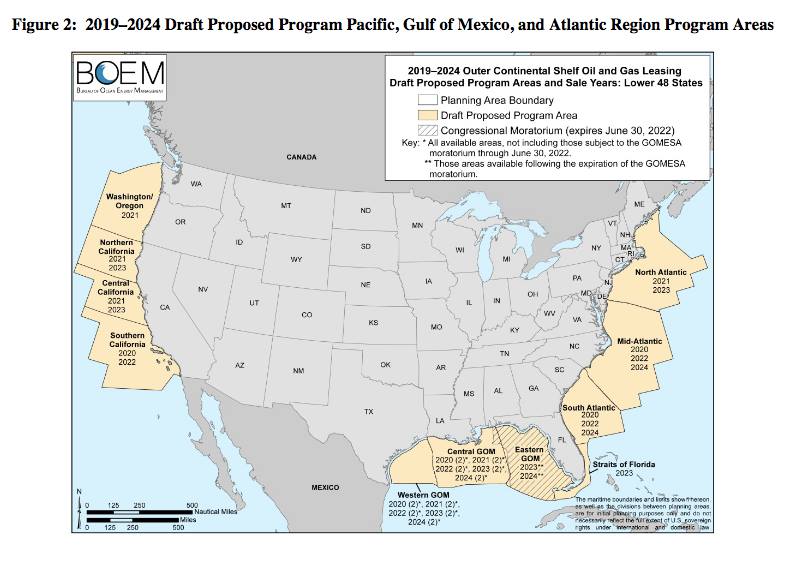

At the same time, the Trump administration has ramped up its effort to open all offshore areas for oil and gas leasing (a map showing planned sales in the lower 48 states is at the top of this post), and advocated more onshore activity as well.

A number of detailed reviews of federal management of oil and gas leases released recently illustrate that the federal government is not doing a great job protecting taxpayer interests in the sale of these natural assets. Poor management results in inadequate returns to taxpayers, elevated returns to private firms, and increased environmental damages. Further assessment would be needed to evaluate whether the pattern of enrichment to private firms maps closely to political giving and personal relationships with politicians, or not. If so, this is the classic example of patronage mentioned in so many of the global studies on natural resource-related corruption.

Twenty years of non-competitive, low return federal offshore leasing

The Project on Government Oversight reviewed lease data from 1997 through 2017 to evaluate long term trends in offshore leasing. Analysts David Hilzenrath and Nicholas Pacifo found that taxpayer returns on offshore lease auctions have been declining over time, that having more tracts open at once results in less competitive auctions (and lower returns), and that more than three-quarters of the federal offshore auctions drew only a single bidder. Only 2% of the auctions had five or more bidders.

The dynamics of weak competition being associated with low bids is not rocket science: any Joe with an e-bay store knows it. Yet to see such well-know market problems playing out on the scale of an entire country's oil and gas sales is highly troubling.

POGO found that a majority (80%) of the leased tracts were also classified as "non-viable," allowing them to move towards auction despite the government lacking comprehensive geologic data on the area. This classification also gave government officials more latitude to accept the "high" bid even if there were few bidders, or to accept the only bid so long as it exceeded a very low minimum threshold.

It turns out that many of these leases were viable after all, with 69% of the tracts from all sales that went into production coming from this non-viable cohort.

The lack of geological data by the resource owner (i.e., the government) might not be a big deal in a situation with many capable bidders. A robust auction process can often generate adequate price discovery. But with a single bidder, the lack of data and ability to accept bids from a sparse bidding field both contribute to taxpayer losses.

POGO's analysis shows that from 1954-1983, offshore auctions generated on average more than 3 bids per acre, and bid payments averaging close to $9,100 per acre leased. In 1983, area-wide leasing was introduced, which opened many acres at once to bidding. Taxpayer returns fell sharply: on average, each acre auctioned since the introduction of area-wide leasing garnered only 1.36 bids, and payments of less than $400 per acre leased.

It should be noted that problems with uncompetitive auctions also apply to federal coal, with similar adverse impacts on taxpayer returns from the sale of natural resources from public lands. For example, the massive Powder River Basin (PRB) coal deposit in the Western US leases most of its acreage using a "lease by application" process where existing producers initiate a request to mine nearby acreage. There is rarely more than one bidder, and the prices gained by the Treasury are low. For more on PRB coal subsidies, go here and here.

The federal resource management agencies do have some history of liking to party. Given the poor economics of dumping all of your supply onto markets at the same time, in a relatively low price environment, with too few bidders to generate competition on lease access even with fewer leases going to auction, and with no consideration on potential impacts on some of the richest fisheries in the US, the administration's current leasing plans are best viewed through the lens of drunken revelry. My home state of Massachusetts alone has the third largest commercial fishery industry in the country, generating $7.3 billion in sales in 2015. This is more than the federal government earned from offshore oil and gas that same year (see table below). No wonder the states are looking to shut the party down.

But the administration doesn't seem to care much about taxpayer return; rather the goal seems to be to pump up domestic supply as much as possible. Rather than ration the leases to achieve better returns on auctions, the Royalty Policy Committee at Ryan Zinke's Department of Interior recommended lowering the royalty rate on new leases. POGO notes that:

Of the 20 primary members, 16 work within the oil, gas, and mining industries or for states and tribes heavily dependent on those industries. Several representing academia and “public interest” groups have ties to industry, raising questions about how much balance they will bring to the committee’s deliberations.

You can read about each member's conflicts of interest at this website. Jayni Hein at the Institute on Policy Integrity at New York University School of Law filed detailed comments against lowering the rates. And, while their arguments (shared by many others) make a great deal of sense, overcoming the conflicts of interest will not an easy task.

What's a little free gas between friends?

Let's say you go to dinner at a restaurant. You are really hungry, so your order two dinners. Turns out, the first one fills you up, and while the second one is equally tasty, you no longer want it. So you tell the waiter at the end of the meal that you just want to pay for one.

Nobody does this. Because they know that the restaurant bought the food, cooked the food, and gave it to you. If you don't use the food, they can't sell it and the value is gone. You have to pay for it even if you didn't eat it.

For some reason, oil and gas companies think the natural gas they take out of public reserves should be different. If they don't stick it in their pipeline but instead flare or vent it, or they simply lose it, they think they shouldn't have to pay royalties on it. But like the wasted dinner, wasted gas is gone. It used to belong to somebody else, and whether you squandered it or your sold it, you need to pay the original owner. There are good economic reasons for this as well: nothing gets wasted more than something that is totally free.

But with the current system, if the extraction firms are getting more valuable oil from the hole, and the natural gas is expensive to process and pipe, they don't want to waste time building pipelines or processing stations before they can pull out their oil. And they think it is just fine to just burn it off the and move on like nothing happened.

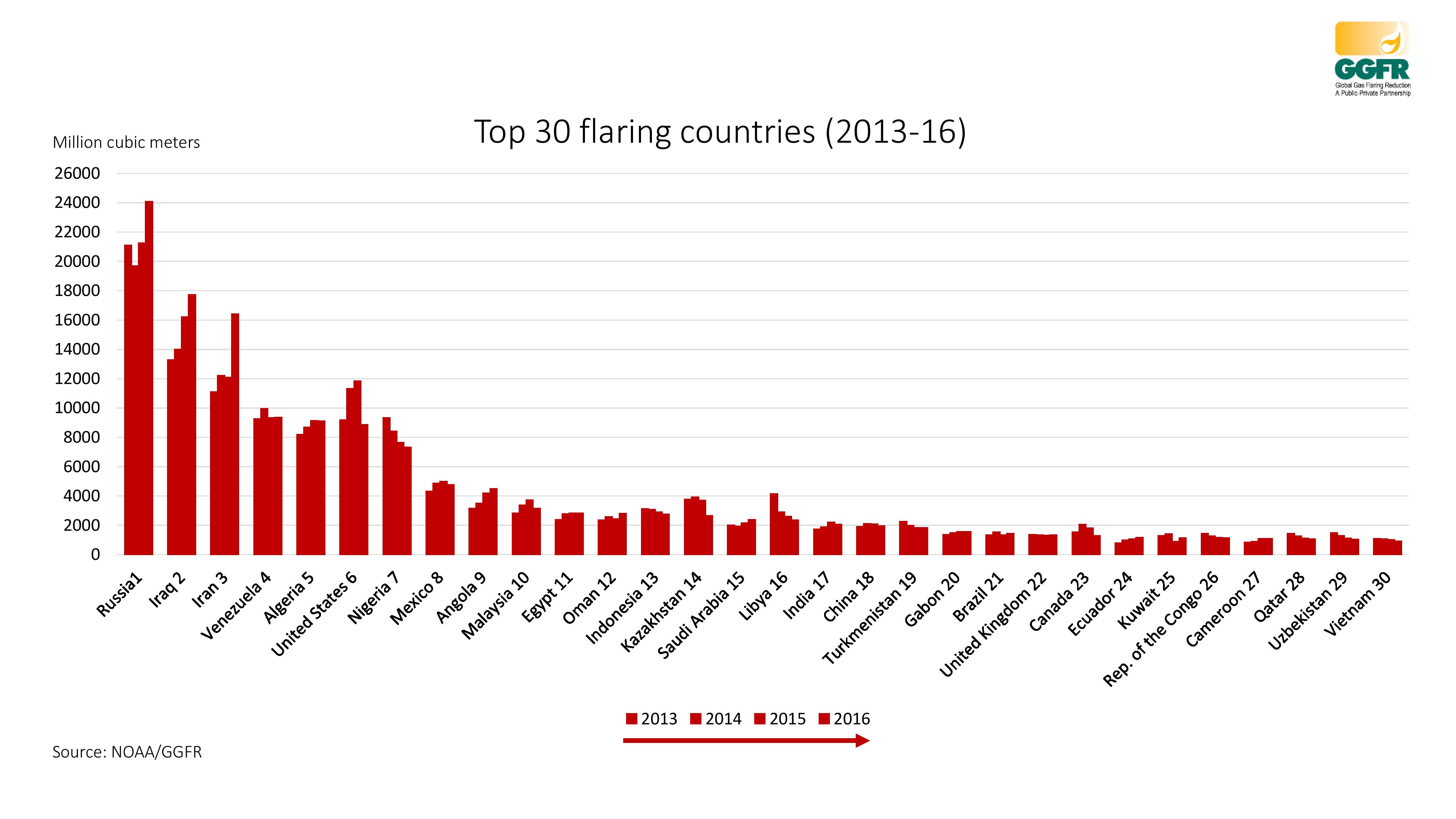

These are not itty bitty bits of natural gas: the push for high value oil in North Dakota resulted in so much gas flaring that it was visible from space, shining as brightly as some cities. It took years to get any regulations in place on flaring in the Bakken, and those regulations continue to be fairly ineffective. In part due to the huge amounts of gas flared in the Bakken region, the US has been among the world's top gas flaring nations for years now -- shifting between 4th and 6th place over the 2013 to 2016 time frame (see graphic below).

And whether flared, vented, or simply lost, if the gas originated on federal lands, much of it was free to the extraction firm. The most recent analysis (Gas Giveaways: Methane Losses are a Bad Deal for Taxpayers) was released by Taxpayers for Common Sense earlier this month. They found that:

- In 2016, royalties were charged on just 16.3 percent of all natural gas lost by oil and gas companies operating on federal lands, down from 29.6 percent in 2015.

- Of all gas lost in the decade 2007-2016, only 11 percent was charged a royalty.

- Overall, oil and gas companies reported losing 25.4 billion cubic feet (bcf) of natural gas in 2016, bringing the total amount of gas lost over the decade 2007-2016 to 209.7 bcf.

- Gas losses from federal lands have increased in recent years. The 2016 lost gas total is more than double the amount reported in 2010, but it is down from the peak in 2015.

- The large increase in annual gas losses from 2007 to 2016 was driven by flaring from oil wells on federal lands. In 2007, oil well flaring composed just 17 percent of total lost gas, compared to 75 percent in 2016, the highest level yet recorded.

- The gas lost on federal lands in 2016 was worth an estimated $75.5 million, while gas lost over the decade was worth an estimated $1.07 billion.

This is not just a federal issue. Since federal leases often share royalties with state and tribal authorities, those government entities also lose out from royalty-free gas. Wells on state lands in key producing states may exempt flared and vented gas from royalties as well. Salzman and Dillon note there are full exemptions in Kansas, Texas, Louisiana, and Wyoming; North Dakota has partial exemptions. State laws may also govern what gas can be charged royalties even on private wells, extending the class of parties who lose from gas giveaways. We can, and need, to do better.