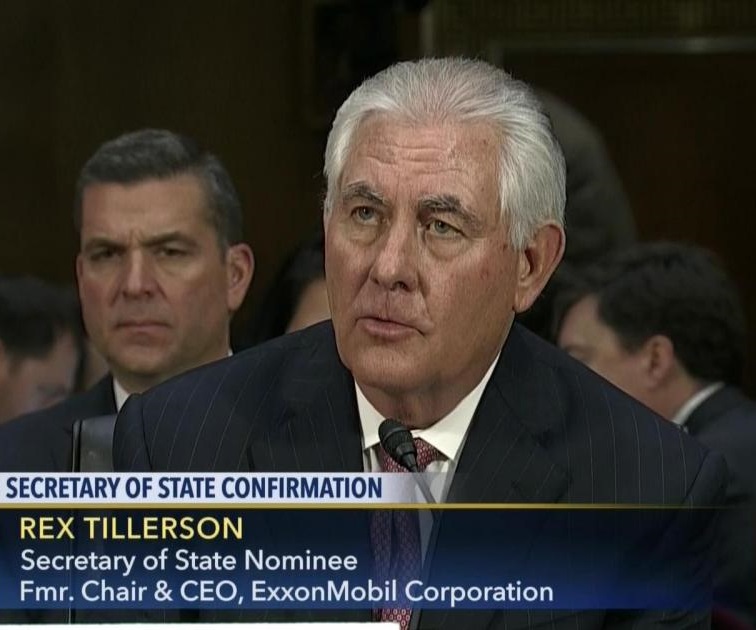

In yesterday's confirmation hearings for Rex Tillerson, the former ExxonMobil CEO stated that

'I'm not aware of anything the fossil fuel industry gets that I would characterize as a subsidy... Rather it is just the way the tax code applies to this particular industry.'

You can review the relevant testimony, and commentary on it by Oil Change International, here.

Denying there are Subsidies Seems a Bedrock Strategy of the US O&G Industry

That Tillerson frames industry subsidies as non-existent is no surprise. In the nearly 30 years I've been working on fossil fuel subsidy issues, denial that government provisions provide them with special support has been a bedrock part of the industry's strategy to keep them.

This is most commonly expressed by their trade association, the American Petroleum Institute (API) -- which spent more than a quarter of a billion dollars in 2014 to defend the interests of its members. Here's how Stephen Comstock, API's tax lead, spun the issue in a 2014 blog post:

Since its inception, the U.S. tax code has allowed corporate taxpayers the ability to recover costs. These cost-recovery mechanisms, also known in policy circles as “tax expenditures,” should in no way be confused with “subsidies” – direct government spending or “tax loopholes.”

Comstock's spin is nearly identical to two decades earlier when API's Rayola Dougher authored a hit piece on a this detailed study on US oil subsidies I co-wrote with Aaron Martin back in 1995. A bit of hand-waving to pick a definition of subsidies they like, dismiss supports to oil sector receives as irrelevant or baseline, and suddenly, as with Tillerson, API concludes if subsidies are above zero, they are so small as to be immaterial. Problem solved.

When other industries get government supports, they are subsidies. Oil & gas? Nah -- just part of the standard way the miraculous thing we call our tax system happens to play out in the oil sector. Of course that system is even-handed across all taxpayers, and not-at-all influenced by the lobbying of special interests.

Other industries need to treat "soft costs" like surveying, engineering, architectural, legal, site preparation, fuel and labor -- critical in the completion of a multi-year asset, though with little or no salvage value -- as part of their investment cost that must be recovered over the useful life of that asset. But if oil and gas investors can write them off immediately as "intangible drilling expenses" -- a huge benefit to their financial returns -- it must again just the way the tax system "applies to this particular industry."

Other industries can deduct from their taxable income only the costs they've actually incurred in the making of their goods and services. Oil and gas get to deduct the market value of their fuel via percentage depletion if it gives them more tax savings -- a subsidy that actually rises when prices for fossil fuels are the highest and any economic case for industry support is at its weakest. It's hard to envision how Tillerson thinks this is normal treatment. For more discussion on the provisions the industry claims aren't subsidies but are, go here.

Subsidies to renewable energy (and yes, even the wind and solar guys acknowledge they are subsidies) are configured to expire frequently so as to prevent them from becoming an entitlement. But if oil and gas subsidies are hardwired into our tax code so they never expire, and have been there for nearly a century in some cases, it must once again be another of those mysterious coincidences of a neutral tax code interacting with the oil and gas sector.

Tillerson's "See No Subsidies" View is Not Reflected by Government Agencies

Despite Tillerson's view that O&G gets no special treatment, this is not a gray area for most federal and international agencies. It never has been.

In a striking example, the Joint Committee on Taxation -- which we rely on to this day to estimate the scale of current tax breaks and provide input to Congressional Members on the expected cost of their proposed ones -- has been flagging the percentage depletion allowance subsidy since the 1920s. The extract below if from a report they published in 1927.

-US Joint Committee on Taxation, Division of Investigation, 1927

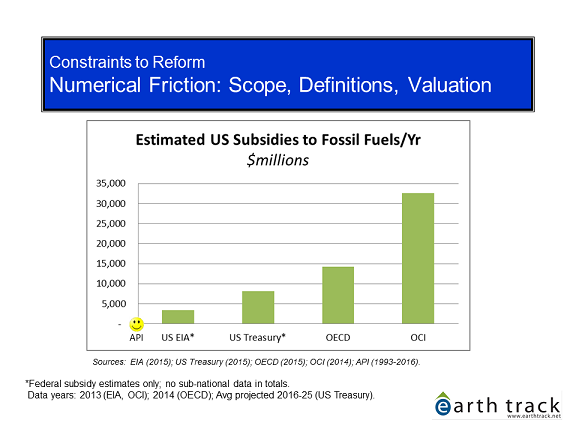

Here's a quick comparison of estimates for the US I put together for a conference late last year that shows (a) other groups believe there are subsidies to oil and gas; (b) the range continues to be contested; and (c) API is a huge outlier in its denial these exist.

Rex's Reading List on US Fossil Fuel Subsidies

There's a fairly long list of organizations that disagree with Tillerson's conjecture that subsidies to O&G don't exist. I thought it might be useful to put together a reading list so he can brush up on the topic. Although many NGOs have done detailed work on this area as well, I know Tillerson will discount that work. Thus, I've limited this list to government agencies.

US Federal Government

International Agencies

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Inventory of Support Measures for Fossil Fuels 2015, US Data. Notes on US Data.

- World Trade Organisation. Overview of the WTO's definition of subsidies.