Fukushima and nuclear power, five years on

It was pure coincidence that the release event for my detailed review of US subsidies to nuclear power -- a document a couple of years in the making -- was on March 11, 2011, the day of the Fukushima accident. I was in DC for the launch, traveling in a cab to the event with David Lochbaum of the Union of Concerned Scientists, who was also releasing a new report.

Lochbaum's analysis examined 14 "near misses" at US nuclear plants during 2010 and how the NRC dealt with them. He is also a world-recognized independent expert on nuclear power and power reactors. His encyclopedic knowledge of the industry was known by many five years ago, and his cell phone rang of the hook as the accident unfolded. Questions from the press and government flooded in, trying to get context on the event, its causes, and how it was likely to play out over the coming days.

Over the past fives years, the nuclear sector in some ways has changed greatly, but in others remained remarkably the same. The sector is still heavily subsidized across the world; still promising innovation will bring costs down to competitive levels; still struggling with delivering on those cost promises on the ground; and still facing little interest in projects by investors.

Within Japan, the accident is still playing out. The stabilization and cleanup of the accident area remains fiendishly complex, as this snapshot in today's New York Times illustrates. And while one silver lining from the accident might someday be a world-class export industry in Japan for advanced robots, at present even the robots are having trouble surviving the harsh conditions.

The human costs of the accident continue to mount -- not just in terms of health, but in broken communities, scattered families, and lost professions. There are some interesting first-person accounts on the GreenWorld blog, documenting meetings and conversations across the affected regions with people still struggling with the after-effects of the accident.

Economists (myself included) tend to focus on things that can be measured and quantified. So before I shift to discuss the numbers, it is important to recognize that much of the suffering that accidents like this cause are not easily quantified. Quantitative damage estimates are a useful proxy for the suffering an accident has caused, but should be viewed as the lower bound to reflect all of the impacts they miss.

Reasonable questions to ask five years on include how the prospects for commercial nuclear power have changed, whether reactors are safer as a result of post-Fukushima requirements, and what the scale of damages from the accident have been. It is notable that key details even of critical, world-changing events, may not be known until years later. A recent article on the Fukushima accident highlights that poor transparency and communications by TEPCO brought the government very close to evacuating tens of millions of people from Tokyo. That's a pretty big deal.

So what's in play? Here's a quick synopsis on three areas: health effects of the accident; costs of the accident; and nuclear economics.

Health Effects

The health impacts from nuclear accidents are always points of contention. Immediate deaths from accident-associated trauma are fairly easy to tally. In contrast, morbidity and mortality from exposure to radioactivity play out slowly over time, can be tough to disaggregate from baseline levels of disease, and are subject to data collection challenges. Because the data matter in terms of political support for current and future reactors, and in terms of the amount and distribution of compensation, getting "clean" data are not easy.

Here is the World Nuclear Association describing the Fukushima accident in a posting updated this month. Basically, they conclude that there is no problem from the accident. But gosh, that government "nervousness" over the accident sure did cause a bunch of hardship and death:

- "There have been no deaths or cases of radiation sickness from the nuclear accident, but over 100,000 people were evacuated from their homes to ensure this. Government nervousness delays the return of many.

- Official figures show that there have been well over 1000 deaths from maintaining the evacuation, in contrast to little risk from radiation if early return had been allowed."

Given that people still don't want to move back to areas designated by the government as safe, WNA's characterization seems a bit simplistic. Ironically, this same article then states that "[m]ajor releases of radionuclides, including long-lived caesium, occurred to air, mainly in mid-March. The population within a 20km radius had been evacuated three days earlier." So one might conclude that the evacuation wasn't so dumb after all.

The WNA also points to the the UN Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR)'s final report of radiation effects in April 2014:

This concluded that the rates of cancer or hereditary diseases were unlikely to show any discernible rise in affected areas because the radiation doses people received were too low. People were promptly evacuated from the vicinity of the nuclear power plant, and later from a neighbouring area where radionuclides had accumulated. This action reduced their radiation exposure by a factor of ten, to levels that were "low or very low."

Radiation expert Andrew Kadam also sees very little risk to human health or even ecosystems. End of story? Probably not. A Greenpeace review of health effects is not quite so sanguine. Soil contamination remains a problem, and they discuss the mental health impacts of the accident and its aftermath. Many of the people in the affected regions still have no plans to return. And the workforce used to do the decontamination is often marginalized and shunned; work violations are common.

Damages and compensation

The United States has less than $15 billion in insurance to cover damages to third parties from a nuclear accident, and we are the biggest pool in the world. The system we rely on, set up by the Price-Anderson Nuclear Industries Indemnity Act of 1957, is actually fairly fragile. The coverage requirements for the policies each reactor must buy for itself have barely kept up with inflation. The majority of coverage comes not through these reactor-specific policies, but rather based on commitments for each reactor to pay money into a common fund over five years, should a major accident occur.

As old reactors close, this pool gets smaller. And even for operating reactors, there are significant counterparty risks that make the availability of funds far less secure. Accidents anywhere cause increased oversight and costs everywhere. Reactor consolidation means that a single parent company could be on the hook for many retrospective premiums at once. These obligations would arise for corporate managers at the same time costs to maintain the rest of their nuclear fleet would be rising. This could make it difficult for firms to meet their restrospective premium obligations. The funds, after all, aren't provided in advance. One need to look no further than recent coal bankruptcies to see how quickly a system of payments reliant almost exclusively on the financial health and solvency of the payors, can go bad.

One thing Fukishima made clear is that available coverage under Price-Anderson is insufficient to cover the cost of any significant nuclear accident. In the US, as in Japan, the taxpayer would end up paying most of the money.

And if we know the pool is insufficient upfront, yet continue to cap liability requirements, this is very clearly a subsidy. Industry always claims it's not; that the incremental subsidy is tiny. If that's the case, end the Price-Anderson cap, and they'll ramp up their policy coverage at almost no cost. Problem solved.

Here's my review of TEPCO's poor liability coverage from March 2011. Five years later, how big have the damages been?

Last year, TEPCO estimated it would pay out $57 billion in compensation costs. James Conca at Forbes, ever the ardent supporter of nuclear, comes out on the low end here. Conca reports a total cost of roughly $75 billion over the next 20 years, only $15 billion of which is associated with cleanup and the remaining $60 billion in "refugee compensation." The biggest cost, he says, is not the accident; its the higher price of Japan's replacement power.

No doubt this is expensive: nuclear utilities in the US routinely buy more insurance to cover replacement power and damages to their own plant than they are required to purchase to cover third party damage from accidents to all of the people and property outside their walls.

But the figures Conca sites need more vetting. They are quite sensitive to the cost of input fuels, and these have plummeted in the years after the paper he refers to was done. Further, the baseline price of nuclear clearly excludes some relevant costs -- adequate accident coverage being an obvious one.

In contrast to Conca, the Financial Times estimates that the nuclear accident has already cost Japanese taxpayers $100 billion, in the form of direct government grants and artificially high power surcharges allowed to make it seem like TEPCO was covering the cleanup costs. NPR notes that "At the government level, the cost of decontaminating houses and farmland in Fukushima prefecture alone carries a $50 billion price tag."

Estimates in 2013 by the Japan Center for Economic Research, TEPCO itself, and other experts rose as high as $600 billion. This included decommissioning of the damaged reactors, compensation to dislocated people, and decontamination of affected lands.

While the final cost is obviously still unknown, these types of projects tend not to come in under budget. Expect a long, expensive slog. And it is clear that post-Fukushima, accident liability systems need not only higher mandated levels of coverage but also a re-think in terms of structure if they are to achieve the dual goals of incenting prudent risk management and operations, and ensuring adequate funds are available to cover the costs of any future accident.

Nuclear Power Economics

Despite investments and a big shout-out for nuclear coming from people like Bill Gates, nuclear fission has not emerged from the wilderness as a viable solution to world energy needs for low carbon fuels. Clearly, Fukushima did not help: a big accident affects the operating environment for everybody else.

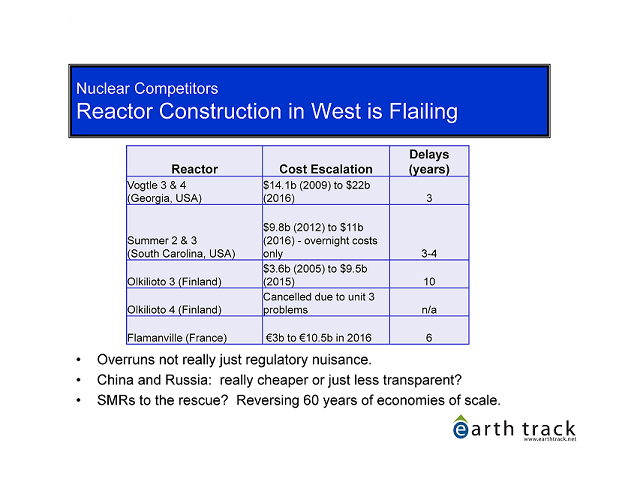

But the pace of innovation and cost reductions are coming faster for nuclear's competitors than for nuclear. New reactor projects are struggling, not only in the West (see below; slides are from this presentation), but also in parts of the developing world as well. Competitively, nukes are not doing well. I expect that to continue.