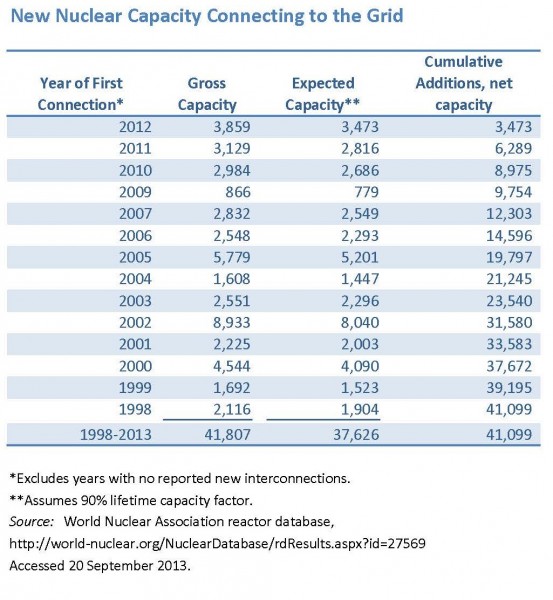

Giving up on "zombie" solar manufacturing plants in China might not be the best solution in terms of dealing with climate change and energy poverty. A Bloomberg review of overcapacity in the Chinese solar sector (Feifei Shen, "Chinese Zombies Emerging After Years of Solar Subsidies") contained some fairly staggering numbers. Foremost was that if the existing solar plants in China operated at full capacity, they would produce 49 gigawatts of panels per year. In contrast, and according to data assembled by the World Nuclear Association, new nuclear power grid connections over the past fifteen years was only 42 gigawatts.

Okay, okay: don't start sending the protest e-mails just yet. The two capacity figures are not totally comparable. Nuclear is dispatchable, and has a capacity factor of around 85-90% depending on its location (and once the plant finally comes online, which is often years later than planned). Solar is intermittent and its capacity factor, according to the US Energy Information Administration, is a much lower 25%.

But even if we adjust the installation numbers by capacity factors, Chinese PV production capacity in terms of expected associated power generation remains an impressive 12.3 GW per year, about equal to nuclear capacity grid additions (at a 90% capacity factor) worldwide since 2007 (see table to the right).

Uses of Zombies

Bloomberg focuses mostly on the overly-generous credit subsidies and other support extended by the Chinese government to overbuild this solar capacity; and how much of it is likely to be shuttered. But China subsidizes all forms of energy (see Earth Track's review of data on Chinese subsidies to fossil fuels prepared for the Global Subsidies Initiative, for example).

Further, zombie assets periodically exist in many sectors of the economy when capital expansion overshoots: chemicals, real estate, primary metals and paper to name a few. When the zombies arise, there are some common patterns that often accompany them: returns to investors drop sharply for awhile, and past investments into capital may never (or not for many years) be recovered as prices across the industry fall to variable costs. But despite the pain, more often than not the excess built capacity eventually wiggles its way into supply chains.

Trying to keep Chinese PV production operating over the long-term could well be a good thing -- though a reduction in the number of firms to have fewer producers each controlling larger production capacity is probably inevitable. Specifically, elevated installations of PV capacity can help address some fairly intractable global problems. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the face of a surge in fracking and a (politically- rather than economically-based) race to drill the Arctic is one important issue, particularly given that there is no indication governments will price fossil fuel externalities into energy markets any time soon. Pricing in carbon, for example, would give a boost to the economics of all low- and no-carbon energy resources.

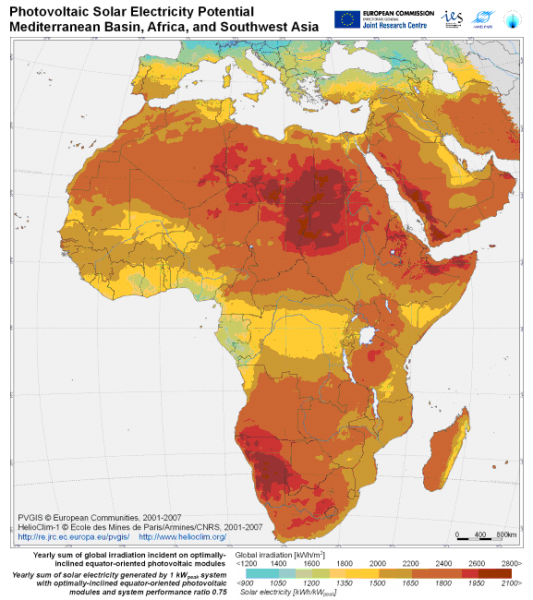

Improving access to high quality power for the world's poor is another. In its 2012 World Energy Outlook[fn]Page 535.[/fn], the International Energy Agency estimated that 1.3 billion people worldwide had no access to electricity, of whom 85% were located in rural areas. Rural locations generally have much higher costs of power transmission and distribution per kWh delivered. This makes grid extensions expensive on a per-customer served basis, though makes off-grid renewables such as PV more attractive. In addition, IEA's data indicated that the group without access to electricity includes two-thirds or more of the population in developing Africa.

The positive news? China is Africa's largest trading partner. And Africa has very favorable conditions for PV power generation (see graphic below from this report):

Modifying "roads for resources"

For the past decade or more, China has been among the largest investors in Africa, building vast swathes of infrastructure. Chinese firms have also been a major buyer of Africa's metals, minerals, and fuels, part of a trade strategy to secure access to a huge domestic demand for raw materials. In our data review of fossil fuel subsidies in China three years ago, it was clear that foreign aid and infrastructure projects were linked to access to foreign oil, though figuring out the financial flows was not possible.

A simple tweak of China's roads for resources strategy could shift at least a chunk of the focus on big infrastructure deals to trading PV installations for raw materials instead. These installations could go to populations most in need of access to safer, cleaner energy sources. Further, the shift might help address some of the pushback that Chinese oil companies are now facing from multiple African nations on the terms of their oil deals and whether or not the trade provides sufficient benefits to the local population. There may be domestic jobs benefits as well. A shift from roads to PV export and installation would be expected to create more jobs right in China, rather than having to export road crews abroad.

Power intermittency less of a problem where current power systems unreliable or non-existent

Although solar power is intermittent, its value in less-developed countries remains strong. First, it can be operated independently of state-owned power suppliers -- often a plus in countries where governance may not work very well, utilities are unresponsive to consumer needs, and grid networks aren't well maintained. Second, it can provide power in remote locations where there is no grid connection at all, or only a connection of poor quality. Third, even among wealthier customers unreliable power supplies have triggered widespread use of loud and heavily polluting diesel generators. Where those locations are remote, the delivered price of fuel can be high. Broader deployment of PV into these regions allows the demand on the generators to drop, reducing both pollution and fuel costs. While generators may still be required for times when the PV generation is insufficient (e.g., nighttime), a reduction in the hours per day on which fossil generators were needed would still be beneficial.