Like favorite sports teams, affinity for particular energy types seems to run deep. Geography clearly plays a role: it is not surprising that Senators Tom Harkin (Iowa) and Richard Lugar (Indiana) have long been staunch supporters of biofuels, and corn ethanol in particular. The two have proposed increasing renewable fuel mandates to 60 billion gallons per year, a move that would result in more than a trillion dollars in subsidies to the biofuels sector over the policy's tenure. For wind energy, there is T. Boone Pickens who has proposed a surge in wind energy to free up natural gas for use in the transport sector (albeit not in our current vehicles which are unable to use natural gas), thereby eliminating the need for much of our imported oil.

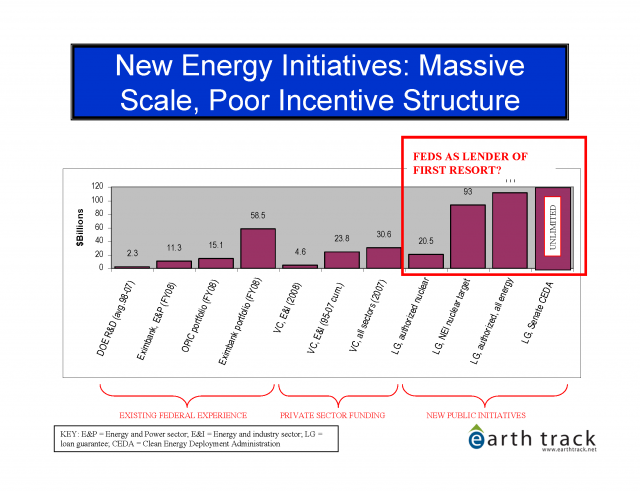

Thus, it is hardly unexpected that nuclear power also has its cadre of boosters. What is interesting, however, is how often these folks tip their hats to France as the model for what the US should do. Senator Lamar Alexander (Tennessee) points to France as he advocates for building 100 new reactors in the country. Alexander, no fan of wind energy, refers to federal supports to the energy resource as "subsidizing sailboats," though assumedly all of his 100 reactors would sport shiny federal loan guarantees on their cooling towers in order to be able to attract financing.

Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina likes the French model as well. And John McCain. And of course the key French government officials are also believers, keen to export their technology not only to the US, but throughout the developing world as well.

Moving beyond generalities of energy independence through nuclear into actual data on the French program is not easy. There is much overlap between military and civilian operations, and the country has not had the degree of transparency on nuclear fuel chain economics necessary to evaluate the cost-efficiency of their nuclear bets. A handful of reports have begun to squeek out providing a broader picture of the French program. Turns out, the model has some flaws that ought to be taken seriously by the US boosters of adapting the approach here.

The most extensive body of work I've seen on the topic has been assembled by Mycle Schneider, an independent consultant and founder of WISE-Paris. His recent reports include a number of interesting findings. First, the French decision to complete reactors when other countries stopped construction due to poor economics led to overcapacity of baseload power in France. To boost usage, the French then subsidized electric heating -- a strategy that boosted aggregate demand, though exacerbated demand swings with heightened demand peaks. Because nuclear power plants must run fill tilt, following a variable demand curve was not something this fleet of reactors did well. As a result, France has had to export nuclear baseload cheaply, while importing peak energy at a much higher cost. The country has also brought back online a number of very old and polluting oil-fired generation stations to provide peak energy.

A second important finding from Schneider's work is that the impact of the nuclear power program on final energy demand has been quite modest, and that the bulk of final demand continues to be met by fossil fuels. He questions the idea that nuclear power was a useful strategy to deal with the issue of oil security, pointing out that only 12 percent of oil consumption in the country in 1973 was used in the electricity sector.

Schneider's "Beyond the Myth" paper also provides a useful review of the institutional framework for the French program, and highlights a number of circumstances where institutional structures have served to restrict rather than enhance program transparency. This history of opaqueness may be one reason why the recent relevations of potential safety problems have caused such a stir.

A second interesting paper, written by Arnulf Grubler of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (October 2009), looks at the costs of the French nuclear program using previously unanalyzed cost data. Grubler finds that France reactor construction times lengthened considerably from an average of 63 months for the 1971-79 period (PWR Westinghouse license reactors) to 126 months for the 1984-1999 period (PWR new French design). He notes that the construction time for the Flamanville-3 EPR reactor submitted by French authorities to the IAEA (p. 16) was "entirely implausible," as it was a shorter time frame (and for a new design) than what had been achieved by nearly all prior reactors built in the country. He also finds that despite standardization, learning, and other factors that in theory can bring down unit construction costs, the French program instead showed real cost escalation over time (p. 25). Between 1974 and 1984, the real cost escalation was 5% per year. This increased to 6% per year from 1984-1990. The latest reactors in the period analyzed were roughly 3.5 times as expensive as the reactors built at the outset of the French program.

An important caveat is that these numbers pick up the cost of fuel chain facilities only through the price of fuel. In fact, however, the French government is itself a major player in those facilities, and these less visible portions of the fuel chain are believed to be heavily subsidized. This would further weaken cost trends from the French nuclear program.

A key justification of massive subsidies to reactor construction in the US is that they are merely transitional supports to help the industry through "first of a kind costs," but will no longer be needed once learning brings reactor costs down. The fact that not even the French saw declining real costs over time is indeed sobering.

A final critique of the French program worthy of mention was put forth by Yves Marignac, the current Executive Director of WISE-Paris, and another long-time analyst of the French program. In recent presentation in New York, Marignac points out that, similar to their US counter-parts, the French have not figured out a long-term solution for managing their nuclear waste; and that very substantial portions of the real costs of nuclear power remain hidden due to state involvement in the sector.

Will a less airbrushed view of the French program make Alexander, Graham, or McCain rethink the most appropriate policies for US energy strategy? Probably not. But it should.