Most people now recognize that the surge in photovoltaic installations across the United States is not just a function of falling panel prices -- though that certainly helped. But there has also been a dramatic pace of innovation in business models that have made putting a PV system on residential or commercial properties much lower risk to the property owner than it was 10 years ago. It is now more similar to buying a large appliance than undertaking an engineering project.

Solar systems can be leased or bought, with guaranteed payments for power production. The technical and financial challenges of technology selection, site evaluation, installation and repairs, dealing with complicated state and federal incentives, and obtaining competitive financing have all been taken on by firms involved in the sector. Incentives are (mostly) aligned so that the firms and the properties on which the panels are being installed share an interest in a long-lived, cost-efficient, high producing system.

But energy efficiency was a different story. Utility programs mostly picked up improvements with very rapid paybacks (insulating attics or upgrading lighting). Firms or other institutions could tap into somewhat longer paybacks through service contracts with providers for shared savings retrofits -- though would need to be confident they were going to stay put for enough years to recoup their costs. But deep energy efficiency -- where more substantive, structural upgrades and investments are made in order to cut energy demand by a third or more -- has been far more limited. That is what makes a new power purchase agreement (PPA) out of Seattle so interesting.

The agreement, between Seattle City Light and the Bullitt Foundation, establishes a 20-year agreement for avoided energy consumption, paralleling conventional PPAs that sell supply. The longer duration makes a broader range of investment possible, though, again, is commensurate with the length of many supply-side PPAs.

The agreement, between Seattle City Light and the Bullitt Foundation, establishes a 20-year agreement for avoided energy consumption, paralleling conventional PPAs that sell supply. The longer duration makes a broader range of investment possible, though, again, is commensurate with the length of many supply-side PPAs.

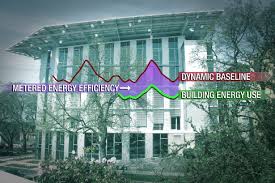

Project participants also note that an improved ability to measure energy savings in real time was also critical in monetizing the savings -- in this case using a meter developed by Energy RM (Energy Resource Management Company) in Portland, Oregon that seems to be a big step forward in being able to track these things.

The new business model for energy efficiency is notable in another respect as well: because the agreement is with the utility, not the building owners, it is easier to bring in outside investors interested in the stream of returns. This can open up financing mechanisms (as occurred in the PV sector) that are entirely separate from the building owner or tenant, and borrowing constraints that they may face.

A first agreement does not a national success make. But the example of residential and commercial PV clearly demonstrates what is possible. Having worked on water conservation issues in multi-family housing in the past, one aspect that intrigues me about the Seattle/Bullit Foundation approach is its potential to address the split incentive problem. In leasing situations, tenants are not in a facility long enough (or don't know in advance that they will be) to justify directly purchasing capital upgrades in order to reduce operating costs. Similarly, because the owners don't pay those operating costs, they often choose less efficient equipment in order to save money up front.

Here's hoping this prototype agreement is copied widely, continually improved, and rapidly scales to become a significant factor in shaping our energy demand and in making our buildings more livable.