While subsidies to fossil fuels are thankfully getting increasing attention, even at the level of the G20 (see paragraphs 24-26 of the link), subsidies to a variety of environmentally harmful activities are pervasive at lower levels of government as well. An Earth Track review of state-level subsidies to biofuels in the United States, for example, found roughly 200 state and local programs supporting ethanol and biodiesel. These programs existed in nearly every state of the country. The Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency (DSIRE), run by the North Carolina Solar Center at North Carolina State University, identifies over 2,000 programs supporting renewable energy and energy efficiency alone.

More systematic assessments of sub-national subsidies, and how they affect natural resource use, are not very common. A useful review of state-level energy tax subsidies was done by Joe Loper of the Alliance to Save Energy more than 15 years ago; I've not seen a more recent treatment of the topic in the US. Evaluations of specific sectors in specific states are also infrequent, though less so. A recent study done by Melissa Fry Conty and Jason Bailey at the Mountain Association for Community Economic Development, for example, does a good job examining coal subsidies in the US state of Kentucky. The analysis is striking in two respects: it illustrates how complex the state-level subsidies are; and it demonstrates that even after one credits the coal sector for direct revenues and those associated with jobs created indirectly from coal industry multipliers, the subsidies still exceed the revenues.

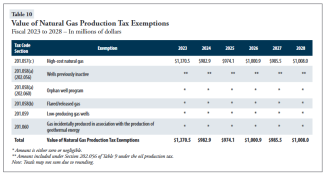

The norm in resource subsidy assessments is to focus on national policy, dismissing the messy world of sub-national subsidies as de minimis. DSIRE, for example, does not monitor subsidies to conventional fuels at all, though many US states also offer them. In site operators do not attempt to quantify the subsidy cost of the programs they do track. The data problem is compounded by the fact that many states do a poor job tracking subsidies themselves. State-level reporting of tax expenditures, for example, is more the exception than the norm.

The Conty and Bailey study of Kentucky coal subsidies is a useful reminder to resist this urge and instead to identify solutions that can improve transparency at multiple levels of government at once. There are multiple reasons to do this.

First, many state and local subsidies are not very effective. They attempt to influence economic activity to migrate from one subidized geographic region to another, creating a "race-to-the-bottom" bidding war that may generate little net new economic activity; or only at great cost. Good Jobs First, a Washington, DC-based organization has been tracking these economic bidding wars for nearly two decades, with many examples of their poor efficiency.

Second, although state and local subsidies often are smaller than those on offer from the federal government, this doesn't mean they are actually small. Consider the Texas Economic Development Act, cleverly structured to allow local governments to offer tax breaks to specific businesses that they don't have to pay for -- the program ultimately shifts the financial burden to the state. A recent audit of subsidies from this program by the Texas Comptroller General (see p. 4) found energy to be the largest beneficiary sector, capturing nearly 60 percent of total subsidies granted to date. The audit found total gross tax benefits of $713 million to renewable energy (for 61 projects), and additional $501 million in subsidies for two planned nuclear reactors.