If newly minted EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt managed environmental risks more similarly to the way he manages the financial risks in his own portfolio, we would be far better off.

He does not. To the contrary, he leverages any hints of uncertainty on environmental damages as a justification to do as little as possible while calling for ever more study. Applied to his finances, such a strategy would leave him invested only in cash as he tried to chase down that last bit of information on each stock before he could buy it. Such a "study-til-you die" approach to investment would lead to years of inaction, growing missed opportunities, and a much-heightened risk of penury.

Thankfully for the security of his retirement and the financial well-being of his family, Pruitt plows into the financial unknown despite his uncertainties. He uses diversification and small investments over many years, to hedge his risks. He does not waste time trying to get every single pick correct, but rather focuses on ensuring the the general direction his investments is the right one.

In the environmental area, Pruitt is an enthusiastic supporter of widespread rollbacks of Obama-era environmental rule makings. The discourse by him and others on these rules implies they were crafted during a quick trip to the loo rather than the result of years of analysis, public comment, and engagement with regulated parties. The current tool of choice for reckless rollback has been the Congressional Review Act (CRA), of which President Trump is already the most frequent user. The CRA prohibits any "substantially similar rules" forevermore after a rollback. Thus, Pruitt's robust support of this strategy indicates his unwavering confidence that not only are existing rules a little bit burdensome, but they are so misguided that nothing anything like them should be promulgated again.

Yet in his financial affairs, Pruitt relies widely on experts to guide how his capital is deployed. He does not second-guess those experts and every decision they've made. Of the twelve separate mutual funds he owns, every single on them is "active" -- in that its expert fund manager is actively buying and selling stocks or bonds in order to beat the performance of the general market segment in which they operate. Pruitt is paying much higher fees for these experts than if he were simply to "buy the index" through a Vanguard mutual fund or exchange traded fund, so he must believe in their strategies.

Unlike his fund managers, environmental experts can't be trusted

On climate change, Pruitt remarked in March that the he wouldn't agree that humans are a primary contributor to global warming. “But we don’t know that yet. We need to continue the debate and continue the review and the analysis.” The Washington Post article mentioning this statement was titled "On climate change, Scott Pruitt causes an uproar — and contradicts the EPA’s own website." Less than two months later, Pruitt solved this contradiction by pulling down EPA's climate change website.

Pruitt was unable or unwilling to name a single EPA regulation that he supported during his confirmation hearings, not even the one that removed lead from gasoline. He said he would enforce the existing Mercury and Air Toxics Standards and the Cross-State Air Pollution rules so long as they "remain in force," though clearly keeping them in force is not a goal. Dave Roberts does a nice job parsing his responses.

But what interests me about Pruitt is how he manages uncertainty in his personal matters versus when it is only other people at risk from his decisions. In future posts, I hope to be able to look at the portfolios of some of the other high-level Trump appointees making decisions that have long-term implications for human health and the environment as well.

Uncertainty is a given; inaction is not

One characteristic of virtually all health and environmental regulations is that there are always many trade-offs between costs and benefits. Often these are inter-generational, with some reduction in current profits incurred in order to avoid (often much bigger) problems that will harm our children or grandchildren. More often than not, these trade-offs are tough to measure precisely. Do nothing and costs remain low for a particular industry. Good for them, at least in the short-term. The long-term impacts may not be as sanguine, as regulatory pressure abroad may force foreign competitors to innovate towards more efficient production systems that end up grabbing market share from US producers.

The environmental down-side is that water gets more polluted, making people sick. Fish catch levels may drop; or downstream municipalities may be forced to incur higher water treatment costs before they can use it. In some situations, municipalities or individuals may have to find and pay for alternative sources of drinking water entirely.

Air pollution continues to cause immediate health impacts in the developing world (more than two million excess deaths a year in China and India alone). In the realm of Scott Pruitt's EPA, damages are thankfully more subtle -- ironically perhaps, largely an outcome of successful US environmental regulations in past decades and overseen by other EPA administrators. Health impacts from air pollution here may take a longer period of time to manifest in asthma, lost workdays, or shortened lifespans. But just because people aren't keeling over on soot-filled city streets doesn't mean these damages aren't real. Consider an impact as simple as coal-powered smog over national parks. Reduced visibility isn't the most dire of pollution impacts, but even here there are damages: tens of thousands of people have taken their valuable vacation days and incurred high travel costs to visit sites that they aren't able to see very well when they finally get there.

The costs of controlling pollution can be tough to measure as well. The first round of cost claims -- the ones that filter into trade journals soon after a new rule to curb pollution is proposed -- tend to be much higher than what compliance actually ends up costing. There are two main reasons for this outcome.

The first is political: affected industries know that compliance will cost them something, and they know that the more stringent the requirements are, the more disruptive it will be both in terms of cost and operational changes. Thus, their immediate strategy is almost always to yell and scream that the pollution controls are not needed because the risks are overstated;This could sometimes be fairly extreme, as with lead additives in gasoline: “...DuPont and General Motors maintained that ‘the average street will probably be so free from lead that it will be impossible to detect it or its absorption’. An intensive industrial lobby was mounted which effectively forestalled any government regulation on lead in gasoline. For example, in response to calls for more research on public health risks, the General Motors (GM) Research Corporation made an agreement with the United States Government to pay for the U.S. Bureau of Mines to undertake such studies. The agreement replaced ‘lead’ with the trade name ‘ethyl’ and included clauses that would bar press and progress reports during the study to ensure that public anxiety would not be aroused. Furthermore, Ethyl Corporation, which was formed by Dupont and GM to produce plumbiferous gasoline, was able to negotiate exclusive rights to comments, criticisms and approval of the results of the study before they were released. With the industry calling the shots, it was not surprising that leaded gasoline received a clean bill of health.” See Jerome O. Nriagu, “The Rise and Fall of Leaded Gasoline,” The Science of the Total Environment, Elsevier, V. 92 (1990), pp. 1-28 and that controls will put them out of business or trigger widespread layoffs at the very least. They will argue that the rules will dramatically disadvantage the United States relative to competitors such as China who are still able to produce like the good old days here: with coal-fired soot blackening the skies.

The second reason the initial estimates skew high is that humans are smart. When people face real costs, study a problem hard, and bring in engineers and managers to play out a bunch of alternative responses, they start to come up with all sorts of new ideas that solve the problem for less money than they originally thought would be possible. Does this always happen? Of course not. But it does happen with most problems, most of the time.

And because environmental requirements frequently incorporate evaluations of available control technologies when they are written; and are phased-in over a period of years so there is time for learning and for the existing capital to wear out before getting replaced, cost impacts are further moderated. The World Resources Institute blog has a good summary of the various claims, and what research actually shows.

While most environmental issues have a clear direction of impact, remaining uncertainty is the norm. This occurs both on the damage side (in terms of timing and specific parties affected if it is not controlled); and with the cost to, and impacts on, industry from the new requirements. Every decision made or not made is shifting rights and costs across the affected parties. This balancing may be explicit (as in regulatory impact analyses) or implicit (as is often the case with long delays in pollution controls that result in years of extra exposure to pollutants).

Every decision made or not made is shifting rights and costs across the affected parties.

These days, the Trump administration has focused on rolling back all sorts of environmental rules that attempt to control pollution, arguing they are just too costly. But the EPA Administrator seems to be forgetting the other side of the cost ledger: how the pollution affects people, natural-resource based industries, and ecosystems themselves. Often the benefits to industry from delay are concentrated, quantifiable, and immediate. The costs of inaction, delay, or rollback are spread across a broad population, come in forms (such as health impacts or ecosystem damages) that are hard to quantify, and involve impacts (such as on health) that take years to play out.

Following Scott Pruitt's money

So how does any of this relate to Scott Pruitt's money?

In his role of EPA Administrator, Pruitt is tasked with making fair trade-offs between the costs and benefits of controlling pollution and protecting ecosystems. He has to make these trade-offs despite residual uncertainty in many areas of evaluation. And he has to do this not once, but with scores of decisions EPA makes about funding, education, and enforcement of environmental goals and rules at the local level. He is tasked with doing this on a state and national levels as well, when implementing new national rules or overseeing existing ones. And he plays a significant roll even globally, through EPA's research on, and engagement with, international cross-border issues such as greenhouse gases and climate change.

Pruitt's private financial portfolio provides an interesting window into how he manages uncertainty and risk when the major impacted party of those decisions is not some nameless neighbor of a big chemical plant in Texas, but rather Scott Pruitt himself and his family.

Do those decisions mirror the way he manages uncertainty and risk across his portfolio of environmental responsibilities, when we are the primary parties at risk? Does it turn out that he is much more careful protecting against really bad downside outcomes with his money than he is with the air we breath and the warming of our planet?

Pruitt's Portfolio: No Golden Bathrooms

Thanks to robust financial disclosure rules that apply to most top federal officials (excluding the President) we get a pretty good picture of how wealthy officials are, what types of assets they own, who's payroll they've recently been on, and who they owe money to. This is incredibly important data by which to ensure these officials are working for us, and not conflicted left and right in their decisions because they've got cash on the line from a particular outcome, either directly or via people they owe.

My key takeaways on Scott Pruitt's finances and risk management:

1) Pruitt is not a wealthy man by Trump cabinet standards

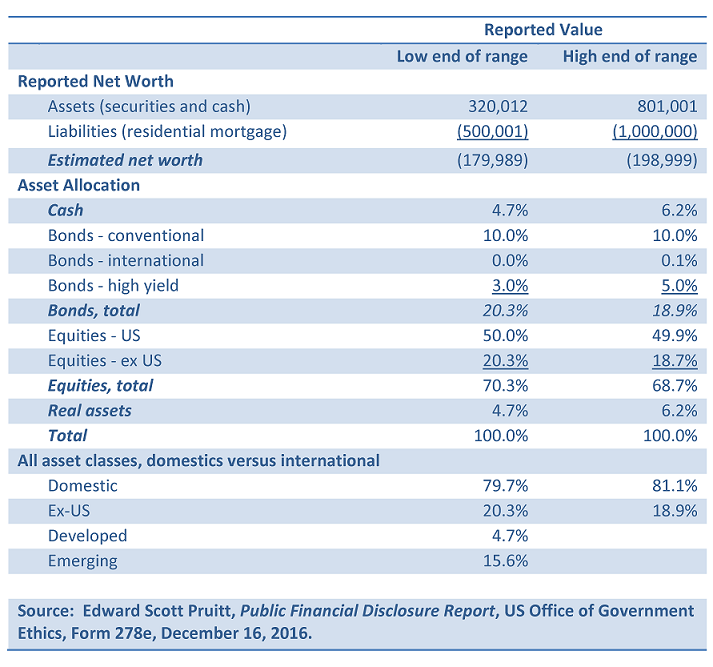

His reported securities, retirement accounts, and cash balances are worth between $320,000 and $800,000. The mortgage on his home is listed at between $500,000 and $1,000,000 -- meaning his net worth may well be negative. As a result, and like most Americans, Pruitt needs to keep working, and to be careful how he invests his money.

Pruitt's federal disclosure does not capture everything (and state disclosure rules for Oklahoma are exceedingly limited). For example, a bank will require owners to put some cash into their homes before it will provide a mortgage. Yet Pruitt's assets do not (and are not required to) list any equity in his home, though he does list a large mortgage. A second area of that confused me was Pruitt's 2010 sale of his 25% interest in the Oklahoma Red Hawks, a AAA baseball team which he first purchased in 2003. According to Tulsa World,

"The sale price of the Red Hawks [at which Pruitt and his partner bought in] was not disclosed, but it is believed to have surpassed the minor league record of $11.5 million paid for the Albuquerque Triple-A franchise three years ago."

A later article put the figure Pruitt and partner paid at a much lower $6.8 million. Sale terms for 2010, 25% of which should have flowed to Pruitt, were not disclosed either. A deal for the AAA Yankees team (albeit a much larger market) around the same time was priced at more than $13 million. Mandalay, the firm that bought Pruitt out of the Red Hawks sold the team four years later for between $22 and $28 million, again suggesting a high sale value received by Pruitt. Regardless of the exact figure Pruitt received in 2010, it is likely that he received millions of dollars from the sale. This should have resulted in a higher level assets than Pruitt reported this year.

Under any scenario, he is a pauper compared to the slate of billionaires on Trump's advisory team. From a risk management perspective, it means that if Pruitt does not properly manage his financial portfolio, he might not have much to retire on: his choices matter.

It also means that he may be more dependent on cash gifts from interested parties to finance any campaigns, and that he may be more susceptible to industry interests if he hopes to work for them after leaving government. Pruitt's potential conflicts of interest between industry and his current role regulating these same industries has been fairly widely reported on, particularly following a court-ordered release of his emails.

2) Pruitt deals with financial uncertainty through diversification, not by inaction

While Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross can plunk down $100 million for a single Magritte painting, Pruitt is making no concentrated bets on particular firms. He holds eight different stock mutual funds, each of which is widely diversified across companies, company size (large and small firms do not behave the same ways during market cycles), and firm location (nearly 30 percent of his stock funds hold non-US firms, with his investments in emerging economies larger than those in developed Europe and Asia).

Pruitt's three bond mutual funds are also widely diversified across individual debt issuers, buffering against non-payment by any one. His real estate investment (aside from his home) is also in a fund with small slices of many properties. Aside from his home, he does not report any other ownership of individual real estate parcels.

One possible explanation for his reported assets being so low despite the proceeds from the sale of his baseball team is that he may have moved assets into the names of his wife of children. Because any public figure of his level faces some liability risks, moving assets to other family members can help hedge against this potential loss. By definition, the strategy will reduce his short-term net worth, and likely his financial options as well. However, one might still pursue it because the asset moves also reduce the risk of a large, negative event (such as losing a legal suit) erasing much of his accumulated gains. Another advantage is that the financial moves provide opportunities to his children and grandchildren that they might not otherwise have had.

So Pruitt isn't sure we're the main cause of climate change. But he does agree the risk is big and we are causing at least some of it. Ought he not then adopt a diversification approach to climate strategies rather than doubling-down on fossil energy? Ought he not be open to strategies that reduce current profits in order to build capacity for a future with lower risk? This is, after all, what he does when his own interests are at stake.

Table 1: Scott Pruitt's Financial Portfolio and Asset Allocation, as Reported in December 2016

3) Using opportunities granted to him by the public sector to improve his financial security

Pruitt recognizes that market whims shift over time, and investors face significant financial risks from under-performance or loss. Where programs exist to help him hedge these risks, he has used them without regret -- even if few people are able to tap into them. Three examples come to mind:

- High salary. As Attorney General of the State of Oklahoma, Pruitt earned $265,650 based on his financial disclosure. It is not clear whether this figure included contributions made to his retirement account; total compensation may have been higher. But even the $265k amount is nearly three times the starting income of Oklahoma's top income quintile during 2016 ($93k). With wealth, of course, comes options. For example, wealthier citizens can avoid environmental harm by paying more in order to live in cleaner neighborhoods. Many of the poor affected by the rules now being rolled back do not have this option.

- Guaranteed pension benefits. Pruitt lists among his assets a "defined benefit" pension plan. This type of plan removes investment performance risks from employees. Much more common are "defined contribution" plans where a set dollar amount goes into an employee's retirement account, and it is up to them to ensure returns are high enough to meet their future needs. Employers much prefer the defined contribution plans because they do not face long-term risks to guarantee a particular benefit level. In fact, the defined benefit plan Pruitt receives is now by far a minority offering in the private sector, with only about 17% of employers providing it as an option. Even for public employees, it is declining in availability. But Pruitt has it.

- Public money to leverage your business. A baseball team needs a ballpark, and in this day and age, who builds ballparks anymore without milking taxpayers? Turns out that Pruitt's Red Hawks relied on a stadium built in 1998 entirely with public money: $34 million of it. He didn't own the team when the stadium was built, but it continued to serve the team while he owned it, and likely boosted the team's value when he sold it.

Managing environmental risks to ensure consistent and continual progress is a critical task of any EPA administrator and important for the long-term health of both our population and our industries. Because Pruitt's management of his own financial portfolio demonstrates a clear ability to make prudent decisions despite imperfect information and many realms of uncertainty, Pruitt's behavior thus far at EPA is all the more inexcusable.