More than most mainstream publications, The Economist has regularly covered energy subsidies and consistently called for their elimination. Too many newspapers pick and choose which subsidies they care about. The Wall Street Journal, for example, rails on subsidies to renewables -- particularly wind and corn ethanol. But government largesse to fossil fuels and nuclear power always seems to be illusory figments of greenie imaginations. Midwest publications too often turn a blind eye on subsidies to ethanol or the corn (and water) that makes it.

The Economist has been more even-handed in trying to get markets working and price signals behind technological transformations. Their January 17th piece "The Oil Crash Has Provided a Once-In-A-Generation Opportunity," focusing on fixing policy failures in the energy sector, is no exception. They call for stripping subsidies to all forms of energy as a way to right precarious government finances and to more accurately price carbon. And on top of simply eliminating subsidies to carbon that flow from subsidies to fossil fuels, they call as well for a carbon tax to address the non-internalized environmental damage associated with today's patterns of fossil fuel production and consumption.

The core of their argument is this:

- When energy prices are soaring, it is hard to boost taxes and eliminate subsidies because consumers are already stretched.

- The falling prices of fossil fuels, along with technological innovations in substitutes, allow a transition to real energy prices to be done at a much lower political cost.

- Politicians should fix energy prices during this window. They should eliminate subsidies to consumers, and they should fix fuel taxes (such as the one in the US that funds our nation's highways) to bring them in line with inflation-adjusted values and current funding requirements.

- Even better would be the addition of a tax on carbon to more accurately align the market prices on carbon-based fuels with their social impacts. "As fuel prices fall," the magazine notes, "a carbon tax is becoming less politically daunting."

The approach makes sense. Indeed, we'd surely be in a better place if these recommendations were to be implemented quickly.

The rub is that the article simplifies both the interactions between energy resources and the manner in which governments provide energy subsidies. As a result, lower prices do not mean that constraints to reform have all gone away. There are three main impediments: subsidy type, the political power of the beneficiary, and subsidy interactions between different energy options.

1) The optimal time to reform subsidies varies by the type of subsidy. For energy consumers (which include large industrial users as well as households), The Economist is spot-on: the time for reform is now. Lower prices create political wiggle room for reform because many energy consumers are less attuned to the rate of decline in energy prices than they are to the fact that their absolute prices are lower than they were a year or two ago. Long-time structural flaws in energy pricing systems -- such as the exemptions that most US states provide to all fuel and power consumers from sales taxes -- should also be corrected so energy is on a equal basis with the other goods and services in an economy.

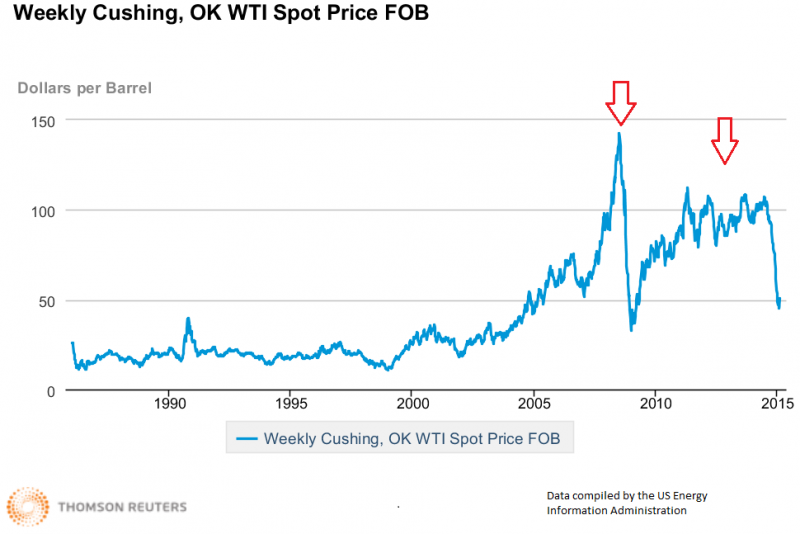

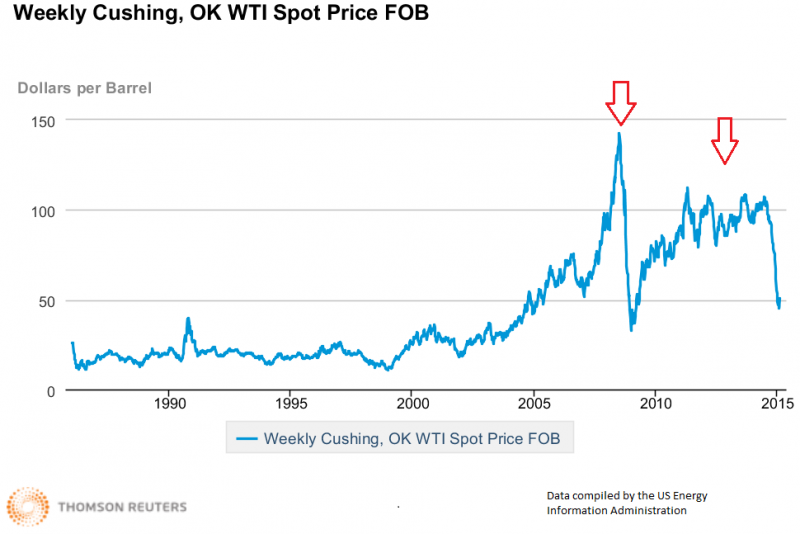

For energy producers, however, the exact opposite is true. The rapid decline in fuel prices has led to financial losses, layoffs, cancelled projects, and growing fiscal distress on the producer side. There were some fat years before today, so we've not yet seen waves of bankruptcies. However, the shift in fortunes has been quick. The opt imal time to have rid ones statutes of producer subsidies was during the fat years (see graphic) when fuel prices were surging: 2007-08 (before the credit collapse), or again the past few years when prices for fuels were again quite high.

imal time to have rid ones statutes of producer subsidies was during the fat years (see graphic) when fuel prices were surging: 2007-08 (before the credit collapse), or again the past few years when prices for fuels were again quite high.

Did our politicians carpe diem? Well, no. In most situations, they missed that window entirely. Their arguments for inaction vary by time period, though it has been inaction all the same. During surging energy prices, they commonly argued (doing their best to do so with a straight face) that nearly all of the supports weren't really subsidies. During the current market environment, the politicians are more likely to focus on the challenging fiscal enviornment for producers and the additional jobs that would be lost from subsidy cuts.

2) Locking in lower subsidies requires political action, but the politics of subsidy reform vary across subsidy types and location. Economics aside, the political environment drives the ability to deliver reforms, and this fact makes it difficult to achieve coherent reforms even within a country, let alone multinationally.

Both subsidy creation and subsidy reform are creatures of political economy. The economics certainly influence the political economy, particularly in the fringes -- such as where the very wealthy are being subsidized or the gross cost of support rises so large that the country is destabilized. But for the majority of subsidies in place today, the political dynamics may run largely independent of the economic benefits of reform.

Consider what seems to be a no-brainer of a reform: boosting the US federal excise tax on motor fuels for the first time since 1993 to stem the growing deficit in highway funding. A rational review of the issue from either political perspective should conclude that increased fees make sense.

Republicans should like the idea of users paying the full cost of the roadways rather than literally free-riding on the backs of general taxpayers. Democrats should like the idea that more highway funding creates construction jobs (often unionized) and makes it easier for workers seeking employment to travel to job opportunities. Both groups should recognize that the purchasing power of the existing tax has dropped sharply, since it has not been adjusted for inflation in more than two decades; that the Highway Trust Fund tasked with building and maintainings the nation's interstate highway system is facing growing shortfalls; and that incremental improvements in fuel efficiency are reducing the excise fee per road-use mile even independent of inflation.

And yet inaction continues to be the norm. Even with the large drop in gasoline prices over the past year, and the clear need, the political will to boost the tax may not exist. Instead, boosting gasoline taxes continues to be a "third rail" of politics -- a reference to the electrified middle rail of some urban subway systems (including here in Boston) that if you touch it you die (or your political career does).

The politics of fossil fuel subsidies to consumers elsewhere in the world are thankfully a bit more mixed. Much of the $550 billion or so that the International Energy Agency estimates flows in fossil fuel subsidies to consumers each year originates with interventions in fuel pricing. The objective is to dampen price increases or to keep fuel prices low. Ostensibly, this helps poor consumers make ends meet, but empirical assessments by the IEA, IMF, and World Bank all indicate much of this support leaks to wealthier consumers.

When prices fall, required levels of public support do generally fall under most of the pricing schemes now in place. This is, of course, a helpful trend for governments who are trying to balance their budgets. But unless the rules behind the price buffering mechanisms are permanently changed during the pricing downturn, the gains will quite often be reversed as soon as energy prices move back up recover. (For a detailed review of price passthrough policies and reforms, see this paper by Masami Kojima of the World Bank).

Changing the rules can be done more easily when prices are low, but that doesn't mean the subsidies are gone for good. If prices surge again, even with altered rules that curb government price caps or other supports, the political pressures to reintroduce the supports grow rapidly. Many introduced reforms ultimately fail because of this dynamic. Case studies, such as those in this IMF study, can help map a reform path that lasts.

Political reform of producer subsidies is almost always challenging as well, regardless of the direction of energy prices. Because the benefits of existing policy are large and the beneficiaries concentrated, the incentive to invest in lobbying is quite large, and recipients invest heavily to delay reforms and expand benefits. More established industries are often better at the political influence game than are startup firms or emerging technologies, and this dynamic is another reason why systemic reform treating all sectors equally (as The Economist rightly advocates) is challenging to achieve in practice. The risk that subsidy reform will affect the newer, weaker industries while defining away the subsidies to the strong is quite real. Even in the Tax Reform Act of 1986, widely viewed as the model for eliminating special interest tax subsidies, the US Congressional Research Service notes that subsidies to oil and gas survived:

While the Reagan Administration did successfully reduce the number of energy tax provisions, the Administration did not accomplish all of their stated goals. Specifically, the primary tax incentives for oil and gas (expensing of IDCs and percentage depletion) were not eliminated, although they were scaled back...[fn]Molly Sherlock, Energy Tax Policy: Historical Perspectives on and Current Status of Energy Tax Expenditures, (Washington, DC: US Congressional Research Service), May 2, 2011, p. 5.[/fn]

3) Subsidy-related cross-fuel interactions. All reforms have winners and losers, and even systematic elimination of fiscal subsidies to all fuels at once can affect industry sub-sectors in very different ways. Here are some examples of the problem:

- New versus old subsidy beneficiary. Support to renewable energy (including some no-so green resources such as ethanol and landfill gas) has been rising sharply in recent years. However, subsidies to oil and gas have existed for 90 years; to large-scale hydro nearly as long; and to nuclear for more than half of a century. Proponents of renewables argue it is unfair to eliminate their support when their competitors have benefitted at the public trough for so much longer. Historical support, they argue, has been baked into the cost structure we see today from their competitors. Yet subsidies need to end a some point, so how does it get done?

- Fiscal versus environmental subsidies. Clearly ending support to renewables without dealing with the environmental impacts of fossil fuels at the same time would be a recipe for failure. This is because environmental damages from the fossil fuel cycle -- whether via ghg emissions or damages to land, air, or water resources -- are a significant factor in the competitive position of these fuels against renewables. This cost advantage would remain even after fiscal subsidies were removed; demand and supply-side options with more favorable environmental footprints would be displaced.

The discussions around subsidy reform often focus on fiscal subsidies alone (spending, credit and insurance, etc.) Yet, if support for renewables is to be removed at the same time as that to conventional fuels, the large external costs of fossil fuels on human health and environmental quality must be addressed concurrently. Otherwise, it will be impossible to achieve the magazine's goal of a neutral energy playing field.

- Legacy subsidized infrastructure. The magazine argues that "the more cross-border pipelines and power cables the better," in reference to political opposition to the Keystone XL pipeline and the export restrictions many countries (including the US) place on energy products. The core logic here is good: price systems ration goods to their highest value uses, and trade allows that rationing to occur on a global scale. But two factors impede this grand vision. First, the legacy subsidies may be what enabled uncompetitive projects to move forward in the first place; absent such support they would never even have been built.

This is both a trade and an environmental issue, as the projects that win as a result may well be associated with imports (undermining local jobs or industries), or with harmful environmental impacts. This issue is certainly relevant to the transport infrastructure to move tar sands to markets: both the Keystone pipeline, other transport lines as well, and to the refineries focused on processing this type of crude. But is is most important relative to the Alberta tar sands themselves, that were heavily subsidized for many years. The issue is also one that appears to be central in the push to drill for oil and gas in the Arctic circle.

Second, the infrastructure associated with the energy exchange may be moving commodities that are not properly addressing external costs, expanding the geographic range of the distortions.

How should this legacy support play into current decisions? Ignoring the subsidies entirely and starting fresh as though they never happened doesn't seem entirely fair. And since pipelines and massive tar sand extraction sites last a very long time, these decisions will exacerbate environmental damages for decades to come.

Eliminating fossil fuel subsidies to consumers now makes sense. Though low fuel prices may give cover to politicians to make such changes now, these reforms nonetheless do need to address issues of energy poverty from the outset, ensuring policies are in place to poorest once energy prices rise again. Otherwise, the subsidy reform "successes" will be short-lived.

User fees should also be brought up to appropriate levels, and clear exemptions from consumption taxes across many countries in the developed world should be eliminated as well. It is also a very good time to establish even a quite low carbon tax -- one that gets the tax system structure right, and grows slowly over time according to pre-established rules that are nearly impossible to derail once in place. These are all no regrets policies; indeed, had we implemented a low, but regularly-escalating carbon tax soon after the Rio conference in 1992, we'd be in a very different place by now.

ill hopefully have time to do a more detailed discussion of the paper in the near future. For the time being, however, it is useful to keep in mind that the IMF's numbers are much larger than other estimates (for example, by the OECD, IEA, and World Bank) primarily because of their incorporation of negative externalities (environmental as well as those related to traffic) and their imputation of baseline taxes on fuels if current levels are too low or non-existent (such as a national sales tax on motor fuels in the US).

ill hopefully have time to do a more detailed discussion of the paper in the near future. For the time being, however, it is useful to keep in mind that the IMF's numbers are much larger than other estimates (for example, by the OECD, IEA, and World Bank) primarily because of their incorporation of negative externalities (environmental as well as those related to traffic) and their imputation of baseline taxes on fuels if current levels are too low or non-existent (such as a national sales tax on motor fuels in the US).

imal time to have rid ones statutes of producer subsidies was during the fat years (see graphic) when fuel prices were surging: 2007-08 (before the credit collapse), or again the past few years when prices for fuels were again quite high.

imal time to have rid ones statutes of producer subsidies was during the fat years (see graphic) when fuel prices were surging: 2007-08 (before the credit collapse), or again the past few years when prices for fuels were again quite high.