A lack of access to modern energy services continues to be a major contributing factor to poverty and human suffering throughout the world. The International Energy Agency estimates 1.3 billion people have no access to electricity, most of whom are located in rural areas. Roughly 2.6 billion people have no access to clean cooking fuels; too often the search for biomass cooking fuels puts the poor, particularly women, at great safety risk as well.

In December, the Oxford University Press published a remarkable volume (Energy Poverty: Global Challenges and Local Solutions) examining the issue of energy poverty from may different angles. Edited by Antoine Halff, Benjamin K. Sovacool, and Jon Rozhon, the book pulls together a wide range of thought on the issue from researchers and practioners.

It was a privilege for me to be able to contribute a chapter on energy subsidies to the effort. "Global Energy Subsidies: Scale, Opportunity Costs, and Barriers to Reform" explores the size and impact of energy subsidies, and presents ways to group subsidy types in order to increase the likelihood of successful reform. The chapter is reposted here with permission of the publisher. You can review other chapters in the volume here.

Global energy subsidies equal at least 1 percent of global GDP

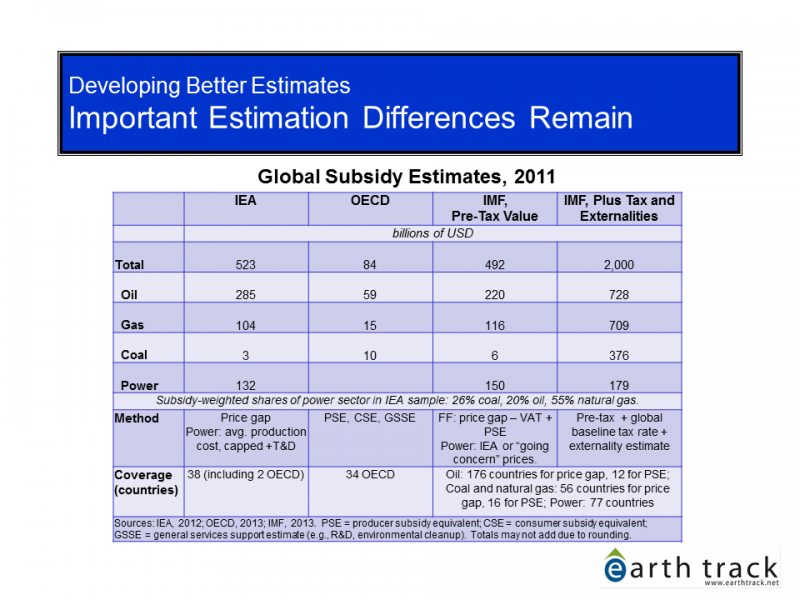

Table 15.1 summarizes recent trends in global subsidy estimates. Staggeringly-large though the numbers be (roughly one percent of global GDP), these figures are likely a significant underestimate. There has never been a systematic global inventory of energy subsidies, and the chapter notes a variety of areas in which subsidy estimates are particularly weak.

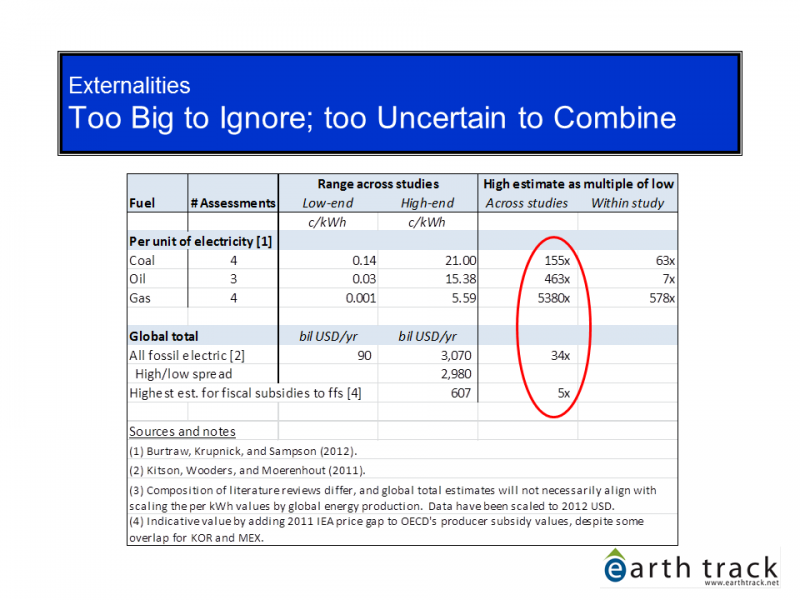

Further, the figures on financial subsidies do not include externalities: the damages to human health and environmental quality caused by energy extraction, refinement, transport, and consumption. Yet externalities are quite large for fossil fuels and some forms of biomass, and clearly allow these fuels to reach market at artificially low prices -- displacing or slowing the expansion of cleaner fuels and improved efficiency.

Data on global subsidies to nuclear power remain sparse. Given a push for $4.4 trillion of new spending on reactors by 2050 noted by the Nuclear Energy Agency (much of it subsized by government credit guarantees), far more extensive data collection on the scope, magnitude, and competitive impacts of nuclear subsidies is sorely needed.

Subsidies crowd out limited public funds from core social supports

In theory, this vast amount of public spending could be going to establish access to modern energy services for the world's poorest citizens. Basic connections to existing energy networks (power, natural gas, or district heat) could be installed; buildings of all sorts could be more effectively insulated and ventilated; more efficient equipment for micro-scale business enterprises could be supported. The opportunity here seems large: annual subsidies to energy are more than 30 times the incremental funding needed to achieve universal access to modern energy services.

Yet, although some of the subsidies do flow in this direction, most do not. Political economy most often drives subsidies towards the powerful and better-connected members of society. This occurs frequently even for policies having a stated aim of poverty reduction. The high "leakage" rates of subsidies to wealthier segments of society has been confirmed in past empirical assessments by IEA, IMF and the World Bank.

The opportunity costs of these policies can be seen clearly in Table 15.2, comparing subsidy cost to GDP, federal revenues (a good proxy for the sustainable budget constraint of national governments), and public spending on health care. Nearly 40 of the countries listed spend more to subsidize energy consumption then what their governments spend on all health care for their populace.

Escaping subsidy "traps" and achieving successful reforms

For the many countries with substantial government intervention in fuel prices, reform is challenging. Efforts to protect domestic consumers or industries often become entrenched and difficult to end. Governments end up 'trapped' into continuing these policies over a long period of time despite high fiscal, social, and environmental costs. The economic and political constraints to subsidy reform tend to feed on each other. Economic factors drive increased political activity, while political activity protects and expands the financial transfers.

Successful reform efforts have involved a number of common themes (see also Table 15.4 in the chapter). Leveraging macro-economic changes to incorporate price reforms can help governments implement reforms during periods that will cause less dislocation. Advance planning is needed, however, so as to be ready to implement changes when conditions are good. Assessing which groups are likely to lose under reform and building in appropriate mitigation measures from the outset, particularly to protect the poor, has been critical in avoiding popular unrest as subsidies are phased out. Integrating subsidy reform more directly with universal energy access targets is also important.

Many existing subsidies have been justified based on claims that they helped the poor; it is only fair to ensure that a portion of the savings is deployed to help achieve that goal. However, just as improperly-targeted government energy subsidies bleed budget capacity away from higher-impact social spending, so too does underpricing of grid-based power or gas erode the ability of utilities to remain viable and expand. Accurately measuring both utility subsidies and cross-subsidies is a first step in fixing the problem. Even if tariffs do not immediately change to target only those who need them, better decisions amongst core options can be made, such as whether to extend grids, to subsidize connection and fixed costs to existing grids, or to reach new areas via decentralized power resources rather than line extensions.

captured everything, or mapped out all of the interactions. But even the first order effort to combine these three main threads is important in gauging winners and losers under the proposals. This is a discussion draft, so email your comments, concerns or corrections if you've got them.

captured everything, or mapped out all of the interactions. But even the first order effort to combine these three main threads is important in gauging winners and losers under the proposals. This is a discussion draft, so email your comments, concerns or corrections if you've got them.