The word out of Switzerland yesterday was that "Iran and and six world powers had agreed on the outlines of an understanding that would open the path to a final phase of nuclear negotiations but are in a dispute over how much to make public." What exactly is the dispute over? The AP noted that

Pressured by congressional critics in the U.S. who threaten to impose new sanctions on Iran over what they say is a bad emerging deal, the Obama administration is demanding significant public disclosure of agreements and understandings reached at the current round. But the officials say Iran wants a minimum made public.

Iranian leaders are opposed to two agreements, saying previous two-stage negotiations were detrimental to their interests.

If we have an agreement and nobody knows the details, we can always claim compliance

Earlier today, word of a framework agreement being reached spread over the internet. The original AP article flagging the areas of dispute pretty much disappeared from everywhere, heading down the memory hole (nearly everywhere; I found one paper still displaying the earlier report and took a screen shot).

In its place, AP's newest update on the successful agreement could be seen. But descriptions of the deal remain vague, and the narrative on the disputes over disclosure disappeared. Time will tell how these concerns were resolved, or if they were just papered over.

Thank goodness for "Congressional critics" on this one, and let's hope the negotiators get it right before the sanctions are lifted. While US sanctions can be implemented again should Iran fail to live up to its side of the agreement, reinstituting sanctions from the broad array of countries now participating will be near impossible.

The transparency issue remains quite important and should not be ignored even if the narrative in the press reports has shifted. There is a rather morbid irony in a country with a special police force (the Basij) focused on identifying and punishing people for the most personal of breaches of a state-defined code of morality,[fn]A brief summary from Wikipedia: "In Iran, Basiji act as 'morality police' in towns and cities by 'enforcing the wearing of the hijab; arresting women for violating the dress code; prohibiting male-female fraternization; monitoring citizens' activities; confiscating satellite dishes and `obscene` material; intelligence gathering; and even harassing government critics and intellectuals. Basij volunteers also act as bailiffs for local courts.'[/fn] arguing that the fundamental terms of an agreement to prevent nuclear proliferation in this important region of the world should be private. The entire line of argument is ludicrous. What you wear, who you are with, and what you read or watch on TV? State business. Basic commitments to prevent nuclear weapons development? Nobody's business.

I mean, why should the rest of us worry that Iranian consent to an agreement with invisible clauses won't actually be followed? Greg Jones of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center has been tracking the Iranian nuclear effort for quite some time. Probably his documentation of past non-compliance, even when the expectations were visible, should be ignored as unimportant. We should also overlook the examples Jones' presents where Secretary of State John Kerry said there was Iranian compliance, but objectively there was not. I'm sure that behavior won't be a factor in the current negotiations, and Kerry has learned from his past over-optimism.

I mean, why should the rest of us worry that Iranian consent to an agreement with invisible clauses won't actually be followed? Greg Jones of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center has been tracking the Iranian nuclear effort for quite some time. Probably his documentation of past non-compliance, even when the expectations were visible, should be ignored as unimportant. We should also overlook the examples Jones' presents where Secretary of State John Kerry said there was Iranian compliance, but objectively there was not. I'm sure that behavior won't be a factor in the current negotiations, and Kerry has learned from his past over-optimism.

And by all means we should also ignore what seemed very much like an April Fool's Day joke headline yesterday -- but unfortunately turned out to be real: "Iran militia chief: Destroying Israel is 'nonnegotiable'," quoting the Basij's commander Mohammad Reza Naqdi. You know how customized those inalienable rights can be across countries... let's just consider this the Iranian version of our own "Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" and move on, shall we?

Proliferation is an externality of nuclear power

Coal power has pollution and mining accidents. Oil has pollution and spills and security chokepoints. Wind has bird kills and corn ethanol pesticide runoff, water and soil depletion, and overuse of antibiotics. Every form of energy has some negative effects, and nuclear is no exception.

In addition to very significant challenges to manage the radioactive wates and periodic catastrophic accidents, the nuclear fuel cycle has the ongoing externality of proliferation. It is not, as many nuclear power boosters like to argue, a totally separate issue and one that should be ignored when evaluating the trade-offs and economics of their fairy-tale massive expansions of nuclear reactors worldwide. Quite the opposite: it is an issue that has been central to the evolution and expansion of nuclear power since the inception of the industry.

The processes and expertise for building weapons and generating electricity are not exactly the same. But they don't need to be for there to be problems. The civilian and the military paths are certainly interlinked, and there is enough overlap that countries frequently use claims about their need for nuclear power as cover for all sorts of other military and geopolitical aims.

There is a strong logic to this tactic. Working on power gives them the time and space to develop equipment, expertise, and professional (or not-so-professional) ties with people in the know. Activities during these years enable them to build the knowledge and technical base that can easily be extended at a time of their own choosing towards weapons. It allows them to distribute production capacity, harden production sites, and establish production redundancies that make military action to roll back programs, should the need arise to do so, much more costly in blood and treasure.

And yet the world pretends this isn't happening, and the "right" to develop "peaceful" nukes is somehow sacrosanct -- more so even than the human rights that the current Iranian government so frequently ignores. This right to peaceful programs is claimed even if the subsidy-free price of nuclear power would be well beyond a level at which the nuclear investments would be justifiable, and at which many other alternatives would easily outcompete nuclear as the marginal source of energy.

This right is upheld even though more rational reading of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) agreement suggests that the "rights" for non-nuclear states to pursue near-bomb capabilities can both be properly limited and properly constrained under the terms of the agreement. Indeed, doing so could short-circuit what has become a decade-long circus of negotiators arguing about whether or not Iran is doing innocent "research," actually building a bomb, or doing research so they can build a bomb quickly when they decide they want one.

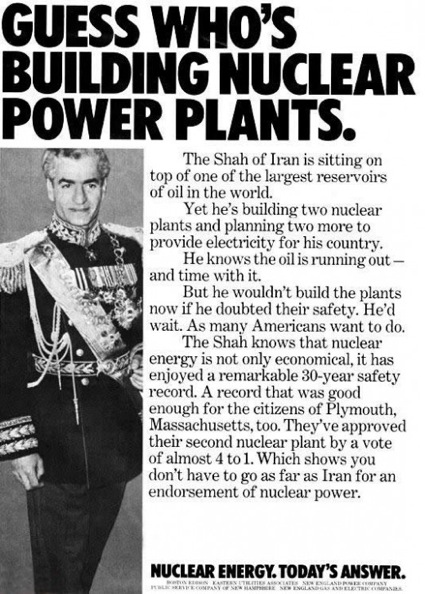

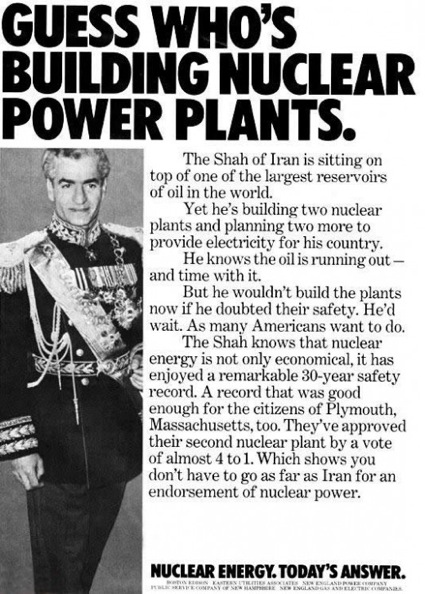

And just for fun, here's an ad from the pre-revolution days in Iran. The ad clearly illustrates the US role in promoting nuclear power in Iran as though it were little more complicated than plopping down a windmill in a farm field somewhere. Nuclear is presented as a resource that, with a little government help of course, can soon come to a neighborhood near you.

And just for fun, here's an ad from the pre-revolution days in Iran. The ad clearly illustrates the US role in promoting nuclear power in Iran as though it were little more complicated than plopping down a windmill in a farm field somewhere. Nuclear is presented as a resource that, with a little government help of course, can soon come to a neighborhood near you.

Historical artifact? Not really. How many countries are playing out this same scenario today -- whether with the US, France, Russia, South Korea, or others as their plant subsidizer? And without any government subsidies to financing, accidents, land, construction, waste management, and decommissioning, how many of these plants would be built based on their own economic merit? It is a question well worth asking.

good to know that they have

good to know that they have

I mean, why should the rest of us worry that Iranian consent to an agreement with invisible clauses won't actually be followed? Greg Jones of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center has been tracking the Iranian nuclear effort for quite some time. Probably

I mean, why should the rest of us worry that Iranian consent to an agreement with invisible clauses won't actually be followed? Greg Jones of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center has been tracking the Iranian nuclear effort for quite some time. Probably  And just for fun, here's an ad from the pre-revolution days in Iran. The ad clearly illustrates the US role in promoting nuclear power in Iran as though it were little more complicated than plopping down a windmill in a farm field somewhere. Nuclear is presented as a resource that, with a little government help of course, can soon come to a neighborhood near you.

And just for fun, here's an ad from the pre-revolution days in Iran. The ad clearly illustrates the US role in promoting nuclear power in Iran as though it were little more complicated than plopping down a windmill in a farm field somewhere. Nuclear is presented as a resource that, with a little government help of course, can soon come to a neighborhood near you.

Some of the key points:

Some of the key points: