Two important, though not particularly cheerful, goings-on to mention.

The first is a new paper that suggests climate change is likely to occur much more quickly, and to be more severe, than previously predicted. This finding underscores a central limitation of so many efforts to analyze highly complex things: we often discover there are really important parts of the system that we didn't understand or didn't even know about, and those gaps matter greatly. This is one reason, perhaps, why the cure for this or that cancer seems always to be "just" five years down the road. Indeed, when a system has as many feedback loops as our earth does, the impact of our blind spots on the accuracy of our predictions is greatly magnified.

You can read the full paperHansen et al., Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2 degrees C globalwarming could be dangerous, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 16, 3761–3812, 2016, doi:10.5194/acp-16-3761-2016. here; or a summary of the core issues it raises in this New York Times write-up. Or, if you just want the bottom line, here's my take:

Remember all of those predictions about how humans were going to screw up the planet, making parts of it unlivable for your descendents, but only long enough after you died so that you wouldn't really know the people who were suffering? Well, now those things are going to happen to descendents you actually do know: your children and grandchildren. Oh, and the changes might come really fast so that there is not very much time to adapt to them.

And you thought economics was the dismal science.

Moving from global destruction to dirty bombs, the latest nuclear security summit is going on in Washington this week. It's core purpose is to contain the risks of nuclear weapons proliferation around the globe, with a particular focus this year on preventing non-state terror groups such as ISIS from getting access to radiological weapons.

The agitation over terror groups with nuclear strategies was heightened by the discovery of surveillance footage of Belgian nuclear plants that surfaced during searches carried out at apartments related to the recent ISIS-claimed attacks in Brussels. Even more worrying, a guard at one of the nuclear plants was also killed and his badge stolen.

US officials seem to be down-playing the find:

But in a briefing with reporters Tuesday, Holgate [Laura Holgate, the White House's senior director for weapons of mass destruction and terrorism] said there was no indication the video surveillance was part of a "broader plan" by ISIS to acquire nuclear materials.

Yup, no worries here. Clearly it makes sense for Holgate to avoid sharing the real data or the fears of the US government on this issue. But the connection between nuclear power and terror worries is hardly new. The UK Parliament did a detailed review in 2004. Here's a more general compilation of documents related to nuclear detection and prevention of clandestine movements of nuclear material from The National Security Archive at GWU going back decades.

Equally long-reaching is this database of historical attacks on nuclear facilities around the world. Created by Gary Ackerman and James Halverson (both at the University of Maryland), the Nuclear Facilities Attack Database is a sobering reminder that nuclear power plants have been targeted many times in the past, and will likely continue to be. Yes, the acronym for their dataset really is "NuFAD," as though there aren't a slew of other fads we ought to try to jump start over attacking reactors...

So: accelerating climate change and nuclear attacks by non-state actors can really threaten the globe. What now? There's a few interesting connections between these issues that warrant some discussion; it would be a shame if attempts to address climate change end up making the proliferation risks materially worse.

1) If you've got big climate troubles then build nuclear?

James Hansen is the first author of the paper on increased climate change risks, and also a leading advocate for a massive buildout of nuclear plants around the world to solve the problem.

On the one hand, if you are concerned about the end of the world, it makes sense to focus on any solution you think can stem the damage. The problem is that the nuclear pathway is slow, expensive, and would greatly expand the risks we face from nuclear proliferation. These challenges, along with references to the related supporting research, are described here. It is critical to remember that both delays in when ghg-reductions are delivered, and strategies that cost more per unit of abatement, both have large opportunity costs in terms of mitigating global risks.

The link above goes through these issues in a fair bit of detail. But I want to focus more on the proliferation angle here.

Far from decrying the need to ramp up reactors quickly, the Brussels attacks are a clear reminder of how lucky we are that the envisioned Nuclear Renaissance of ten years ago has moved at a glacial speed (in its pre-global warming original meaning, not the accelerated melting we're seeing now...) Personally, I am glad the we did not see a blossoming of a reactor in nearly every country, as seemed a feature of the push for ever-more new-builds in the mid-2000s that was hyped by governments and reactor manufacturers alike.

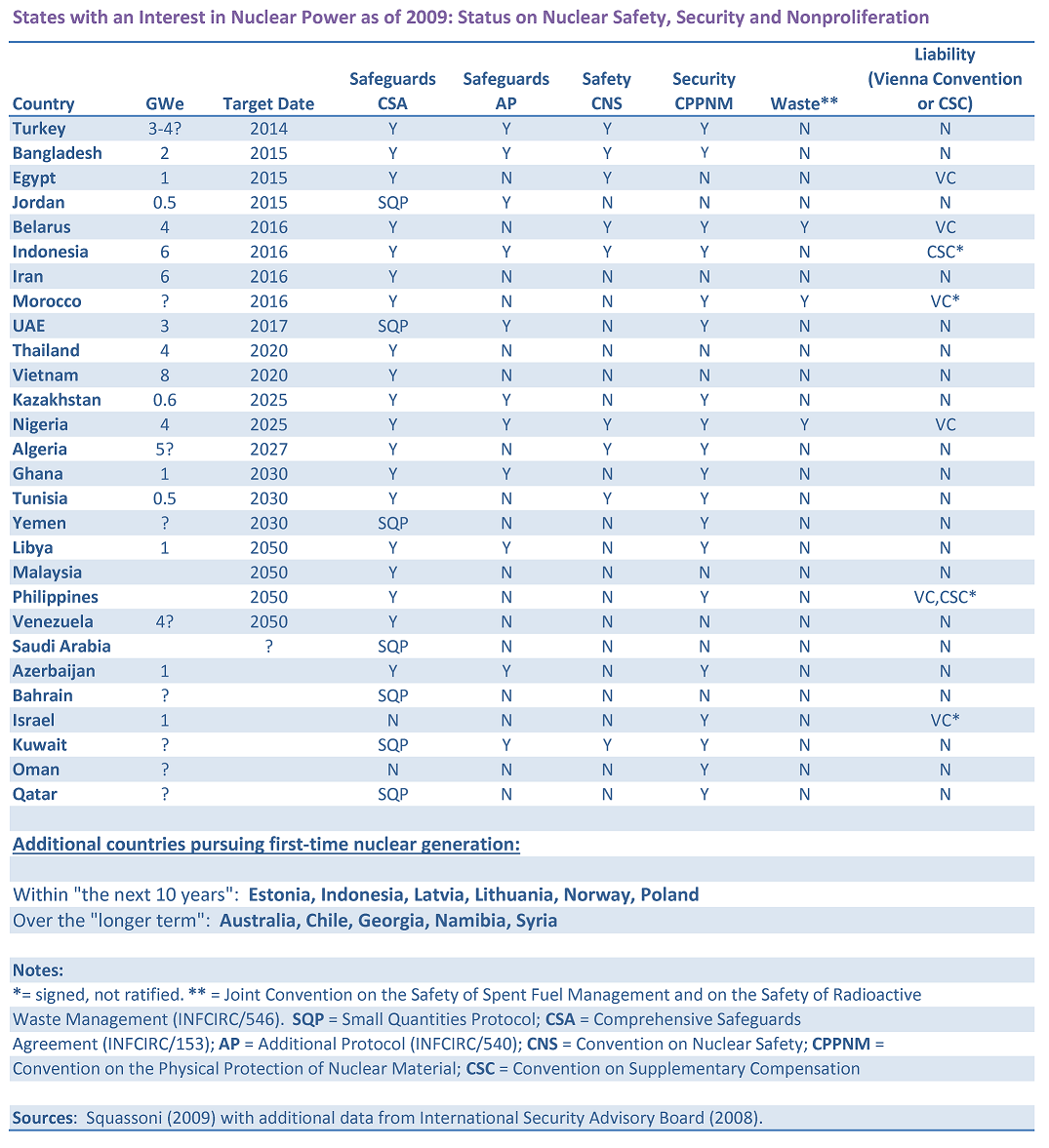

For a trip down memory lane, the chart below summarizes which countries were looking into getting their first nuclear power generation capabilities at that time, and how ill-prepared they were to enter this realm.

The chart is mostly from Squassoni (2009),Squassoni, Sharon. "Nuclear Power: Ho w Much More?" working paper prepared for the Nonproliferation Policy Education Project, March 2009. although some additional countries were added based on a report for the US Department of State by their independent International Security Advisory Board (2008).International Security Advisory Board, Report on the "Proliferation Implications of the Global Expansion of Civil Nuclear Power," April 7, 2008.

A first key takeaway from this table (larger version available here) is that the gaps in capabilities to handle the complexities of the reactors were huge. Most of these countries had not signed on to existing safety and security agreements, let alone possess the capabilities and intent to effectively implement them. Most had no formal plans on how to handle their radioactive waste, and all had fairly weak accident liability coverage or none at all.

Which nations were teeing up new nuclear capacity in 2008 and 2009 that we should be glad didn't get it?

Most of the countries roiled by unrest and civil war following the Arab Spring (including Syria), for a start. And Venezuela, which has sadly but steadily been failing to provide more and more basic state functions and faces endemic corruption. And parts of the former Soviet Union that are certaintly not democracies, and have low government transparency and accountability. Consider these bullets dodged; and another reminder of why global nuclear expansion is not at all the same thing as scaling up solar panels.

But don't we have an obligation to offer all of these countries -- indeed, any country that wants it -- access to nuclear technologies and power under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty? Most likely "no" -- particularly when other non-nuclear approaches to address both energy needs and climate change are cheaper.

2) Taxing greenhouse gases sure would be a whole lot simpler

There really ought to be bipartisan consensus on doing simple things that start us along the path of addressing climate change by sending better price signals to markets. This can be a first step of a system that gets refined over time; but the inability even to take that first step is quite troubling.

Yes, theoretically one could massively build out reactors across the globe, using gobs of public money over decades and decades. But you could not do so without crowding out less expensive ghg abatement; and you could not do so without dramatically ratcheting up the concerns over dirty bombs, near-bomb-ready nations, and diverted materials.

In contrast, taxing carbon could pretty much start immediately in the United States. And even though prices of carbon-intensive fuels would rise, resultant energy prices would still be lower than they were a few years back. Revenues raised would be large (the US Congressional Budget Office estimated about $120 billion per year), though absent revenue recycling, the tax would be regressive.

But revenue recycling could and should allow the carbon taxes to displace other taxes that are more distortionary, improving the cost-benefit ratio of the approach significantly. In its review of the many options to recycle revenues, the CBO found there was quite a large variation in the degree to which different schemes would boost welfare, productivity, or mitigate the economic costs from carbon taxes on affected parties.

One general conclusion was that reductions in the tax rates on businesses and individuals would mitigate a sizeable portion of the impacts of a tax. But that

using the revenues to cut marginal tax rates on corporate or individual income would benefit the economy more broadly but would probably have limited value to low-income households, who typically owe little, if any, income tax (p.12).

This conclusion seems premature: income taxes are not the only deduction from the take-home pay of low-wage workers. Indeed, since many of these workers owe little or no income taxes (due to provisions such as the earned income tax credit), it is these other fixed charges that likely comprise the biggest contributors to the spread between the gross cost of labor to an employer and the after-tax funds that employees end up with to live on.

Mandated contributions for social security and medicare are an example of this class of deduction. These costs include not only the amounts deducted from employee paychecks, but also the share "paid" by employers. The economic incidence of the employer portion is generally believed to fall on workers (depressing equilibrium wages) even though the employer actually writes the check. Increasingly, mandated medical benefits would fall into this category as well.

Revenue recycling by reducing these fixed charges at the low-end of the wage scale could be an attractive option, and making up lost contributions to these important programs using carbon tax proceeds. Such a shift could further boost the benefits to the welfare of low wage workers from any of the discussed increases in minimum wages. Alternatively, it could partially offset the wage increase needed to reach a target standard of living. Because conservative groups often oppose boosting the minimum wage, some type of trade such as this could achieve the same level of after-tax wages for lower income workers while facilitating the implementation of carbon taxes in the US.

3) Climate deniers want certainty on human contributions to climate change before taking any action; yet routinely act under uncertainty in their personal financial portfolios

While the logic of a carbon tax with revenue recycling is quite strong from an economic efficiency perspective, any type of carbon constraint doesn't work politically if people simply don't believe climate change is happening, or (the increasingly common argument for inaction) that humans and human-related activities are causing the observed changes.

Few things in this world have absolute certainty. But it is certainly strange that the same people who routinely dismiss concerns over warming and the need to take any action by arguing that the science isn't "settled" also routinely do take action in their own financial portfolios despite a great deal of unpredictability and uncertainty. In their financial dealings, they know they will be much worse off by doing nothing. But the exact same logic applies to our climate system.

Here's a look at two prominent legislators who adamently deny a need to deal with climate change, and for whom the Center for American Progress has already done the legwork in finding strident "quotes of denial". I've put their quotes first, followed by a review of their financial portfolios as disclosed via their Personal Financial Disclosure Forms.

Senator, and Presidential Candidate, Ted Cruz

The last 15 years, there has been no recorded warming. Contrary to all the theories that they are expounding, there should have been warming over the last 15 years. It hasn’t happened … You know, back in the ’70s — I remember the ’70s, we were told there was global cooling. And everyone was told global cooling was a really big problem. And then that faded.” Sen. Cruz has continued to raise doubts about climate satellite data, and he held a Senate hearing titled “Data or Dogma: Promoting Open Inquiry in the Debate over the Magnitude of Human Impact on Earth’s Climate.”[New Republic, 11/6/14 ||| Washington Post, 1/29/16]

So the answer to uncertainty on the human impact on climate is, well, do nothing. But in his personal finances, Cruz has adopted a widely distributed portfolio of funds to keep costs low while diversifying all sorts of financial risks into thousands of underlying positions that vary by type of asset, industry, company size, and geography.

So the answer to uncertainty on the human impact on climate is, well, do nothing. But in his personal finances, Cruz has adopted a widely distributed portfolio of funds to keep costs low while diversifying all sorts of financial risks into thousands of underlying positions that vary by type of asset, industry, company size, and geography.

Also of interest -- in the very few places where he continues to make concentrated bets on individual stocks, this is almost entirely with sizable holdings in oil and gas firms.

Here's Senator Cruz's most recent financial disclosure form filed in July 2015. All of these are accessible on the extremely useful Open Secrets website. What we see:

- Because Cruz's wife works at Goldman Sachs, it's not a big surprise that nearly all of the funds he's in are Goldman-run. Without the family connection to Goldman, he'd likely be able to find equally good but lower cost options to accomplish the same financial goals (e.g., Vanguard and Fidelity).

- Cruz's diversification in fixed income (bonds) is broad and includes both corporate and municipal high yield and regular bonds, adjustable rate bonds (often many financial firms), international bonds, and shorter-term instruments that carry less interest rate risk.

- Cruz's diversification in equity funds is similarly wide, including domestic stocks with some specific allocations to growth companies and to smaller cap firms. Internationally, he has both developed and emerging market stocks, as well as a targeted stock fund for Asia. A Japan-only fund from earlier filings is no longer in his portfolio.

- Targeted portfolios are also a central part of his planning strategy. These funds include a mix of growth-oriented assets (i.e., more stocks) until a certain point in time such as the start of college (via 529 plans) or target date retirement funds. As the target date (at which cash will start to be withdrawn) approaches, the portfolio manager ramps down the share allocated to higher risk equity assets and replaces it with more cash and short-term bonds. Cruz uses low-cost providers such as Fidelity and USAA, mostly in aggressive growth portfolios, for his childrens' college funds. His retirement vehicles include a mix of diversified domestic and international stock portfolios, as well as two target date retirement funds, one for 2035 and one for 2040.

- The oil and gas sector has been among Cruz's largest campaign donors.

So: very wide diversification across and within asset classes to hedge his investment risks. This includes many bets outside of US markets, despite what one could assume is Cruz's primary allegiance to US firms and US jobs. Cruz does have some actively-managed investment funds via Goldman Sachs, so believes that Goldman will outperform the market even in highly liquid and transparent sectors such as US equities.

Other than shares held in Goldman Sachs itself, the only individual stocks he owns are all in the Oil and Gas sector. (Goldman Sachs, by the way, very much believes that climate change is real, and has targeted capital investments of $150 billion by 2025 into mitigating strategies such as clean energy.)

- Holdings of $15,000-$50,000 per firm: One Gas, Inc.

- Holdings of $50,000-$100,000 per firm: Oneok, Inc.; Chevron Corporation; Plains GP Holdings LP.

- Holdings of $100,000 - $250,000 per firm: Exxon Mobil Corporation; Enterprise Products Partners, LP.

Cruz's first financial disclosure filing in 2011 shows that many of these firms were in his portfolio prior to his first run; and also lists many of this clients prior to running for Congress which is interesting in its own right. However, it is notable that nearly all individual stocks outside of oil and gas have been sold in the intervening four years, while nearly all oil and gas holdings have not been. Individual stock positions in 2011 not showing up in his 2015 filing include: Dominion Resourses, AT&T, McDonald's, General Electric, Coca Cola, Pfizer, Microsoft, Verizon, JP Morgan, Bank of America, and Costco.

Summary: If Cruz applied a similar hedging strategy to our climate as he does to his personal wealth, he would accept a moderately-sized carbon tax as a way to more effectively align market decisions on all sorts of long-lived energy-related investments with what even he would likely agree is a non-zero probability that human activity is affecting climate systems. One doesn't need certainty to begin to take prudent, hedging actions.

It is also likely that the preponderance of individual stocks being in oil and gas firms (total value as high as $750,000) may contribute to his inaction.

Senator, and Senate Majority Leader, Mitch McConnell

“For everybody who thinks it’s warming, I can find somebody who thinks it isn’t.” More recently, when asked whether he agreed that human activity was driving climate change, McConnell responded, “I’m not a scientist.”[Cincinatti Inquirer, 3/7/14 ||| ThinkProgress, 10/3/14]

McConnell states he's just not certain about what's happening with the climate; maybe it's a problem, maybe it isn't. But the same inability to have perfect knowledge in his finances (maybe emerging market stocks are going to implode; maybe they are going to surge as growth expands) hasn't stopped him from engaging with the market and hedging the uncertainty through widespread diversification.

McConnell states he's just not certain about what's happening with the climate; maybe it's a problem, maybe it isn't. But the same inability to have perfect knowledge in his finances (maybe emerging market stocks are going to implode; maybe they are going to surge as growth expands) hasn't stopped him from engaging with the market and hedging the uncertainty through widespread diversification.

Similar to Cruz, the vast majority of his holdings (as of 2014) were in mutual funds and exchange traded funds spanning domestic and foreign stocks and bonds; small, medium, and large cap sizes; and gold. Gold investments do best when economies are in turmoil; McConnell has invested in gold to diversify the risks of his portfolio, despite his likely goal and direct responsibility for helping the United States and the global macroeconomy stay healthy.

The focus on well diversified funds has been a constant in the McConnell portfolio since his first filing in 1995.

He and his wife (she appears to hold the bulk of the combined net worth) do continue to believe in the ability of active funds to beat the market index in a wide range of equity segments despite the higher fees and tax cost of these active strategies. Unlike Cruz, McConnell makes greater use of the lowest-cost Vanguard funds,Increasing empirical evidence shows that active fund managers across a wide range of asset clases are unable to beat the market over any extended period of time; and that their higher management fees along with the higher taxes that their frequent trading triggers for investors, result in lower after-tax returns to investors than simply owning a low-cost index fund or ETF. and shows no holdings in individual oil and gas firms. Potential conflicts of interest would come via corporate services provided by, and directorships held by, his spouse. However, these are not in the oil and gas sector so do not see relevant to the global warming issue.

Summary: McConnell is hedging uncertainty in financial markets using a widely diversified, low cost investment strategy. Applying this approach to climate change, he should also support the introduction of a moderate carbon tax to hedge climate risks to the economy, and to allow that hedging to occur in the most cost-efficient manner possible.