The mysterious Q Division in the James Bond movie franchise was always on hand with inane, though coldly effective, inventions that would save Bond and defeat even the most diabolical enemy. In the magic of the movies, a bit of public money directed towards the R&D staff of the British Secret Service always seemed to save the day.

Subsidizing CCS: Good intentions aren't enough

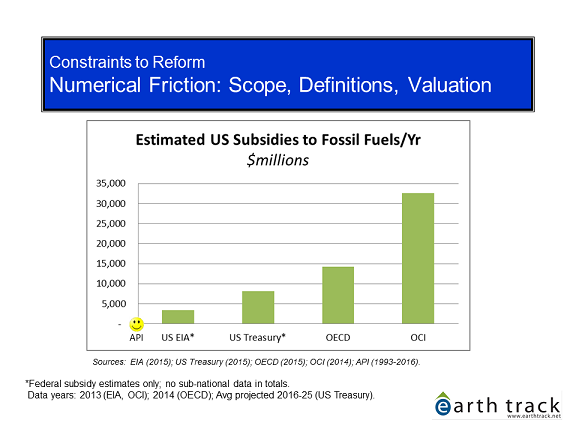

Perhaps it was Bond fans in Congress who lobbied for the creation of Section 45Q of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). For those of you who don't read the tax code over breakfast, 45Q provides a $20 per ton tax credit ($21.85 for 2015, after inflation adustments) for capturing CO2 from industrial operations and injecting it into the ground. And while this posting focuses on 45Q, the provision is but one of a fairly long list of federal and state subsidies to carbon capture and sequestration that shift liability, directly subsidize CCS projects and storage, and guarantee purchases from plants capturing carbon. While the stated justification may be to wean society from too much carbon pollution, the effect of these subsidies is to prop-up carbon intensive industries such as oil and gas extraction while undermining the competitive position of low-carbon alternatives.

CO2 already has some market value. It is often captured at oil and gas well sites and reinjected into the ground as part of enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques. And though the country can't seem to get its act in order to restrict carbon emissions, EOR has long had its own tax break. The injections boost well pressure, facilitating extraction of additional valuable hydrocarbons. Section 45Q combines this existing practice with industrial capture: so long as one is collecting CO2 from industrial sources rather than as a byproduct from oil and gas drilling, you can still get a tax credit (albeit a lower one) for directing that carbon into existing oil and gas fields.

The IRC refers to this as "recycled carbon dioxide," and injecting it for EOR generates a tax credit of $10 per mt ($10.92 in 2015 after inflation adjustments). Under present law, the tax credits apply to the first 75 million mt of CO2 sequestered from eligible facilities -- about half of which have now been used up.

Biggering the subsidy trough

Industry and other groups have argued that burdensome provisions of 45Q have slowed the uptake of the subsidy, and that the lead time on new projects results in the current tax break being effectively expired since qualified credits will largely be gone when new projects come on line.

The National Enhanced Oil Recovery Initiative (NEORI), convened by the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions (C2ES) and Great Plains Institute, has become a major coordinating body for expanding federal subsidies to CCS. For the past few years, NEORI has advocated changes to the law that would:

- Increase the ability for firms to tap into the tax credit.

- Increase the subsidy per mt of CO2 captured.

- Increase the number of tons eligible to claim the credit.

In combination, the changes would greatly increase the subsidy to CCS. NEORI has framed the changes as generating net revenue increases. However, the assumptions they used to reach this outcome are a bit problematic -- largely that you'd get enough new oil and gas on which to charge taxes and royalties to offset the CCS subsidies; and that somehow that extra O&G wouldn't be incremental to existing demand, but rather would offset fuel streams even higher in carbon.

As residual capacity under the existing rules wanes, industry has begun posturing for more support. They argue that many more subsidized projects are needed before CCS can stand on its own. A handful of legislators are listening, though not surprisingly this group includes members from states that will benefit immensely from increased EOR and EOR-related subsidies. They have proposed new legislation to extend and expand the CCS support.

The Conaway Bill (R-TX), HR 4622, would make the subsidy permanent; give as much credit to EOR as to permanent storage; and sharply increase the value per ton (from $20 to $30/mt for underground sequestration and from $10 to $30/mt for EOR). A proposal by Reps. Heitkamp (D-ND) and Whitehouse (D-RI) would reward non-permanent sequestration such as EOR at a lower rate, but in absolute terms would boost the tax subsidies sharply to both categories: to $50/mt for permanent sequestration and $35/mt for EOR or other "utilization" strategies such as growing algae for biofuels using waste CO2.

NEORI's Brad Crabtree seems open to anything that provides more subsidies to the NEORI constituency. Bigger, longer tax breaks are on the list of course. But so is allowing CCS enterprises to use the Master Limited Partnership structures that have been so valuable to oil and gas companies by eliminating their corporate income tax burden. He advocates using tax exempt private activity bonds for CCS endeavors as well, and even government intervention in oil markets to provide price stabilization (expensive CCS becomes an economic nightmare when fossil fuel prices fall).

Given that the firms NEORI hopes to bolster are often massive, with perfectly good access to capital markets all on their own, this entire push seems a bit odd to me. Occidental Petroleum, the owner of the largest current CCS project in the US (the Century Plant in TX) had a market cap of $60b as of August 2016 -- despite suffering from the decline in oil prices in recent years. If it had to pay a tax on all of its CO2 emissions, you can be sure they would invest appropriately in CCS; taxpayers don't need to do it for them.

Subsidizing pollution abatement: a noble objective with harmful side-effects

The debate over subsidizing pollution abatement is a long-standing one.Indeed, this is a debate I remember having with former NEORI co-convener Judi Greenwald more than 15 years ago, when she was at the Pew Center on Global Climate Change. If the government is subsidizing something that reduces ghg emissions, should it be counted as a subsidy to fossil fuels, or as a "beneficial" subsidy to a green economy as one might look at tax breaks for insulating ones home?

Should one measure impact within a narrow set of options (e.g., conventional coal versus more efficient coal combustion techniques) or against the whole range of options that exists within an economy over time (e.g., coal versus energy efficiency, or a new long-lived coal plant today versus energy options ten or twenty years out)? The duration matters because many subsidies lock in public support for an extended period of time (NEORI's 2012 proposals would award each project ten years of eligibility, and continue to provide subsidies to new CCS projects at late as 2040; some pending legislation would make the subsidies permanent) for capital that lasts even longer. In contrast, the certainty of predicting any technical improvements gets markedly worse the further into the future one goes.

Those supporting large subsidies to abatement, including NEORI, generally frame their argument as a necessary evil. The ghg problem is so big, and CCS so central to any viable solution, that the government simply must step in to help things along. There's no time for taxpayers to dither on bringing this technology forward (though usually the lack of investment by the firms themselves is overlooked). The final element of this argument a claim that, in reality, the public investment needed won't really be very big. There will be job gains, multipliers, royalties on the new EOR, and so on. Supporting evidence may be thin.

Yes, any spending will generate some economic activity, and it is frustrating to see a problem that needs attention but to have politicians and firms do little. But overall, the "necessary evil" approach misses more than it captures.

While dynamism in the pace of government-subsidized CCS technology breakthroughs is assumed and promoted, subsidy proponents underplay both the downsides of the subsidies and the dynamism of alternatives:

- The negative effects of CCS subsidies on competing sectors are understated.

- Too much of the assumed positive effects are attributed to the CCS subsidy program, rather than shifts that would have happened anyway.[fn]The NEORI review includes a sensitivity run of "additionality" in which they assume only 90% of the increase in EOR is due to the tax credit, rather than 100%. Not much of a range considering that carbon constraints could well be part of the policy mix during the next 10-20 years and coal is already losing market share in the US at a rapid clip.[/fn]

- Political economy is ignored and governments are assumed to be both efficient and objective.

- Solution pathways are defined too narrowly.

As a result, these assessments tend to dramatically underestimate the benefits of a broader-based, price-signal-led response to the challenge of reducing greenhouse gases. Political earmarks relative to price signals become ever less effective as the number of ghg-reduction pathways grows, the subsidy duration increases, and the complexity of the system (i.e., our economy) rises.

A better path to lower carbon

The counter-argument to subsidizing ghg abatement, which I strongly support, goes as follows:

1) No silver bullet. There are many pathways to address greenhouse gas emissions, and elected officials (particularly elected officials subject to fierce lobbying) are unlikely to have any solid basis to know which pathway is best over a short-time frame, let alone one that runs for decades. Further, even a technical review of options currently available has a fairly high probability of being wrong as new information, innovations, or deployment and scale-up challenges come to the fore.

2) Polluter should pay, and the price of pollution-intensive products should rise. The industries triggering most of the problems ought to be feeling the most economic risk from changing business circumstances that could put them out of business. This pressure is one of the only ways to get them to invest at an appropriate scale to modify their operations. Further, the market pressure adeptly forces disciplined deployment of capital in ways governments struggle to achieve, accelerating the development and uptake of new approaches.

As of a couple of years ago, and despite surging profits, the US coal industry had largely punted on spending its own money to secure its own future. A detailed compilation of coal industry financial performance versus investment in new technologies released by the Center for American Progress in mid-2009 found roughly 2 cents of every dollar of profit was reinvested in trying to develop the technical improvements that would allow coal to survive economically in a carbon-constrained world. And even here, nearly all of the projects relied on substantial public co-funding. Total quantified private funding on CCS projects was only $3.5 billion; total profits for the period 2003-08 were nearly $300 billion.

With coal industry profits way down since, and many of the large firms in or near bankruptcy, spending on CCS is unlikely to have improved. But if the problem isn't important enough for company executives and shareholders to put their cash on the line in order to save their companies, how can one rightfully ask taxpayers to do it?

3) Pollution control costs should almost never be subsidized. Except in the case of acute and severe risks to human health and the environment (e.g., toxic spills, nuclear accidents), governments ought not subsidize emissions or emissions controls. Rather, they should constrain emissions robustly and consistently, forcing the cost of controlling that pollution into the price of the related goods and services. Even in the case of acute events, payments should be collected retroactively from the polluter if at all possible.

What is surprising is how often politicians and presidents want to replace the Polluter Pays Principle with a policy of PCGS: 'Powerful Constituents Get Subsidies.'

This framework is hardly path breaking: according to one paper, the polluter pays principle (or PPP, which is essentially the approach I advocate) entered the economics literature in the 1920s. It was adopted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (now a global leader in tracking fossil fuel subsidies) in the early 1970s. What is surprising is how often politicians and presidents want to replace the PPP with a policy of PCGS ("Powerful Constituents Get Subsidies").

Polluter Pays Principle ignored in NEORI push for more subsidies to CCS

I accept NEORI's argument that right now the economics of CCS in large industries and power plants don't support massive investments into capture and CO2 pipelines. But this point is secondary (and easily fixed by constraining carbon). My core concern is that NEORI is mis-framing the carbon problem and who should be responsible for fixing it.

If a lead smelter emits pollutants into the air, these damage human health and the environment and we restrict the emissions. The result? Emissions drop and the cost of lead rises. Plants invest in better pollution control; markets shift away from lead where they can -- some in the short term and more over time as technology evolves; lead recycling may rise; and some facilities that are too old to justify large new investments simply go out of business. Yet for some reason when the pollutant is carbon we're supposed to treat emitters as supplicants rather than as businesses that need to clean up their act.

From a narrow, static view of markets, subsidizing carbon capture and sequestration may seem like a promising transition policy. Proponents argue that it helps firms get on the right path and provides an impetus to develop new technologies. They argue that building the infrastructure to capture and move CO2 is expensive, and that even if subsidized CO2 is being used to extract more CO2-containing oil and gas, the technical learning is worth it.

Yet for some reason when the pollutant is carbon we're supposed to treat emitters as supplicants rather than as businesses that need to clean up their act.

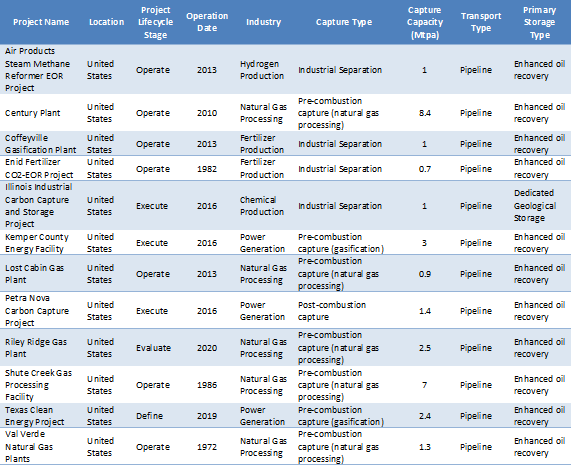

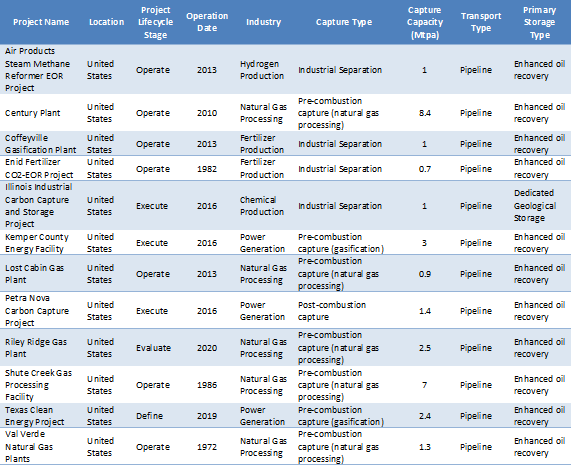

These same arguments were used to justify billions in subsidies to corn ethanol, though the support did more to crowd out more advanced but more complicated cellulosic fuels than usher them in. CCS appears at risk of a similar fate: Table 1 below shows that virtually every project in the US is for EOR, not permanent sequestration; no wonder the oil state legislators like CCS subsidies..

And because there are many options to achieve the end-goal of lower carbon across our diverse economy, tax breaks such as 45Q end up subsidizing carbon-intensive fuels and industries -- and large scale operations at that, since small emitters can't generate enough credits to finance the collection and transportation infrastructure. By harming the competitiveness of much lower carbon strategies and technologies, the subsidies actually prolong the service life of the carbon-wasting production systems.

Sure, coal with CCS is better ghg-wise than conventional coal plants; but it is still much worse than wind, solar, or nuclear from a carbon-perspective (and existing coal projects with CCS aren't exactly going well). It would be better simply to force carbon prices into the market prices of carbon-intensive goods and services, leveraging the competitive position of low carbon substitutes instead of undermining it as the tax credits do.

If ghg reductions are cheaper in one sector than another, we ought not to care -- buy the cheapest ones first. Instead, proposals such as NEORI put forth a couple of years ago establish carve outs for reductions by sector, ensuring that high cost sectors get bigger subsidies.

When subsidies to CCS span decades, cost billions of dollars, and occur in a world where residual CO2 emissions remain free, potential arguments that they are mere demonstration projects cease to be relevant. Virtually every economist, and, indeed, most elected officials, recognize that broad-based carbon constraints are the most efficient way to bring down greenhouse gas emissions. If elected officials are too weak or afraid to implement such constraints, that does not mean we ought to sign on to subsidizing pollution control costs for major industrial plants.

Table 1:

CCS Projects in the US: It's Really all About the Oil

Global CCS Institute, accessed 8 August 2016, https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/projects/large-scale-ccs-projects#map

Subsidizing carbon capture to boost carbon emissions from existing (subsidized) oil fields

Let's move back from general principle that we shouldn't subsidize pollution control to the specifics of 45Q that does just this. Consider that the feds are providing nearly $11/ton in tax credits to reinject captured CO2 into oil and gas wells because it ostensibly removes the greenhouse gas from circulation.

Yet the clear purpose of EOR is to free up more oil and natural gas from the ground, which in turn is burned to release more unregulated greenhouse gases for free. Even proponents of large new subsidies to CCS for reinjection don't see this policy as a slam-dunk. In fact, they say that climate sees a a net gain only if

EOR [enhanced oil recovery from injecting the captured CO2] is replacing 'dirtier' barrels of oil. If the United States used one more barrel of oil from EOR, and one less barrel of oil from a more energy-intensive source such as oil sands, these experts [Judi Greenwald, who formally ran the National Enhanced Oil Recovery Initiative and Sean McCoy at the IEA] reckon, there is a net benefit to the climate. They caution that these kinds of estimates are very difficult to pin down.

NEORI's 2012 proposal did not seem to stipulate lower subsidies for CO2 flows used in EOR versus direct sequestration. It also offered credits under an auction approach that they estimated could hit $37 per mt.

Recent legislative proposals are even more generous. The bill introduced in the house by Reps. Heitkamp and Whitehouse would more than triple the current credit to EOR, as well as making the same $35/mt tax credit available to other CO2 uses such as growing algae that also result in associated carbon emissions later. The $50/mt granted to permanent sequestration in 2025 is pretty much in line with EPA's social cost of carbon estimates for that time period, underscoring the ability to incentivize similar market behavior by growing a political spine and taxing carbon.

Net ghg reductions likely elusive. In the real world -- where oil extracted anywhere gets burned somewhere, I would suggest that the purported net ghg reductions will be elusive indeed. Despite sharp declines in oil prices and raging wildfires in Alberta, tar sands production is down but still substantial. A team at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory evaluating the EOR issue for the US Department of Energy was equally skeptical, also noting that special tax breaks for enhanced oil recovery had already provided subsidies of close to $2 billion for injecting CO2 into oil wells. Indeed, Jennie Stephens of Clark University argues that CCS subsidies are an impediment to dealing with climate change because they slow higher value investments into carbon abatement.

Main beneficiaries on the industry side also in fossil fuel industry. Who benefits from the subsidy is also important to look at. We know that oil and gas extraction activities will benefit from larger volumes of less expensive CO2 to inject. But what types of industrial sites are producing so much CO2 from their operations that it will be economic for them to capture the CO2 and a build pipeline to move that CO2 to where it can be injected for fun and profit?

Economies of scale in recovery suggest that larger emitters would be the most likely beneficiaries anyway; but the current statute actually requires this. 26 USC 45Q(c) defines a qualified facility in part as one "which captures not less than 500,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide during the taxable year." By definition, these are firms for which 45Q helps to subsidize compliance with carbon constraints.

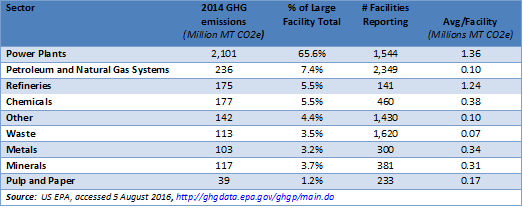

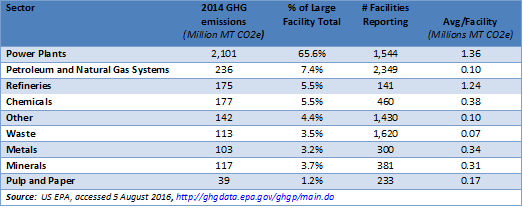

Table 2 below summarizes the main potential winners from an expanded 45Q based on US EPA data on ghg emissions from large facilities in 2014. One should not be surprised that the biggest industrial winners are power plants (they by far dominate the large facility emitters as well as the largest average emissions per facility) and refineries (second highest emissions per facility). It's a twofer: the same subsidy benefits not only oil and gas extraction sites, but large downstream industries in the coal and oil sectors as well. EPA emissions data allows sorting by facility, so one can actually generate a list of the roughly 950 or so large emitters that meet the 500,000 mt/year CO2 cut-off.

Petroleum and natural gas systems, though large emitters per EPA data, would likely not be eligible for tax credits under the current terms of 45Q.

Table 2:

Coal Power Plants and Petroleum Refineries are Largest Beneficiaries of CCS Subsidies

captured everything, or mapped out all of the interactions. But even the first order effort to combine these three main threads is important in gauging winners and losers under the proposals. This is a discussion draft, so email your comments, concerns or corrections if you've got them.

captured everything, or mapped out all of the interactions. But even the first order effort to combine these three main threads is important in gauging winners and losers under the proposals. This is a discussion draft, so email your comments, concerns or corrections if you've got them.