It's been almost two years since Earth Track and Oil Change International released a detailed review of oil and gas subsidies to Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs). The paper documented the favored exemptions that MLPs receive from standard corporate tax rules and how they primarily benefitted oil and gas companies; the increasing use of IRS private letter rulings to broaden the range of activities able to shelter natural resource-related income from corporate taxation; concerns that efforts to expand eligibility to renewable energy would also dramatically expand exemptions for fossil fuels and conventional electric power generation; and the possibility that the revenue losses from MLPs were being greatly underestimated by the federal government.

Growing push to move energy assets off the corporate tax roles

The key pressures driving "MLP-ification" (an apt term popularized by an equity research team at Goldman Sachs) remain: an effort to bypass corporate income taxation for large swathes of energy assets, while still allowing access to public equity markets through listed shares. The tax-bypass challenge isn't just limited to MLPs, and is raising increasingly important policy questions regarding tax collections and cross-sector tax neutrality. This matters to economic development because political decisions are creating differential tax burdens by industry; and it matters to renewable energy and climate change because the vast majority of the publicly traded energy enterprises escaping federal corporate income taxes are in the fossil fuel sector.

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) also allow publicly-listed partnerships to avoid corporate level taxation. Like MLPs, tax-favored REITs have been around for decades. Yet, a similar process of IRS rulings have gradually broadened the definition of eligible property: most recently, power transmission assets have entered the pool of REIT-eligible assets. The chart below, developed by Professor Felix Mormann (University of Miami and Stanford), succintly summarizes this expansion (full set of slides here):

Another new entry to tax-favored energy structures is the "YieldCo," an MLP-variant that bypasses limitations in MLP eligibility to open corporate tax avoidance to solar, wind, and hydro assets as well. While not technically exempt from corporate income taxes, the YieldCo structure forms a "synthetic MLP" to avoid corporate taxes using expenses and high depreciation deductions.

There is no doubt that all of these structures reduce the cost of capital and/or boost margins for eligible players. But while the energy sector is an important part of our economy, it is not the only part or even necessarily the most important part.

Tax favoritism for some types of assets or industries over others introduces political bias into which economic sectors succeed. If one wishes to argue that any taxation of corporate income is inefficient and should be replaced with other mechanisms of raising revenues, that may well be a debate worth having. But using an arbitrary or politicized process to exempt energy or real estate enterprises from corporate taxation while other worthy sectors face normal tax rates is hardly a logical underpinning for the competitive market that the US purports to be.

Recent trends show continued growth in MLP assets, and increased use of other favored corporate structures for holding energy assets as well

Here's a brief review of some of the major MLP-related themes emerging since our paper was released:

1) Eligibility continues to expand; IRS proposed rule puts brakes on some sectors, though challenges likely. The number of private letter ruling requests to the IRS on whether particular income streams qualified for MLP status rose sharply, reaching well more than 30 in 2013. Despite the growing number of requests for rulings, in the vast majority of the cases the IRS ruled in favor of the petitioners. As a result, the number of firms and industries successfully able to avoid corporate income taxes through the MLP rules grew steadily. As the number of petitions continued to rise, however, the IRS decided a more formal evaluation was needed. The Service released a draft of those guidelines on May 6th.

Although the rules remain open for comment, a number of early conclusions are being drawn:

- Paper industry-related MLPs, once considered an impending extension of those created for fossil fuel activities, no longer seem likely. The IRS has argued that because paper requires additive processing of wood and pulp (e.g., the addition of chemicals), it would fail one of its eligibility tests. Other timber-related activities that don't require chemicals or other substances to manipulate the properties of the wood would be remain eligible -- saw mills or bark mulch production, for example. Thomas Ford of Andrews Kruth LLP argues the published interpretation is a material change in IRS policy, reversing a private letter ruling from two decades ago.

- Companies that sell fuels in bulk to airlines or government customers would produce eligible income; general retailers would not be. Fuel terminalling and storage can be organized as an MLP as well.

- Fuel refining eligible for MLP treatment is not entirely consistent in the IRS proposal. Olefin production was deemed eligible under prior letter rulings, for example, but appears to be excluded now (existing MLPs would get a 10 year transition period). Production of natural gas liquids would be eligible if the product was also found naturally in petroleum fractions, but not (as with methanol) if it is always manufactured.

- Many fracking support operations remain eligible, so long as they are recurring, central to well production, and specialized. Water delivery is not, so could not be organized as an MLP. However, water service companies that remove and treat water as well as deliver it would be.

Sidley Austin LLP notes that

The Proposed Regulations appear designed to establish uniform and balanced standards for determining qualification across various types of activities, while remaining true to the directives of the legislative history to the enactment of Section 7704(d)(1)(E). Nonetheless, perhaps constrained by the legislative history, the Proposed Regulations reflect a substantial amount of arbitrariness in the application of the announced standards, and set forth industry-specific applications of these standards.

I'm not fully fluent in lawyerese, but the undertones here seem (and in comments from other law firms) seem clear: industry challenge of the IRS proposed rule is likely. And, despite some restrictions on MLP growth, it is also clear from the IRS proposed rules that a growing set of functions in the fossil fuel production and delivery system will remain eligible to operate as tax-exempt MLPs. Further, by eliminating the need for a private letter ruling, the process of asset conversion to tax-exempt MLPs may actually accelerate after the IRS regulations are finalized.

2) The market capitalization of tax-exempt MLP fossil fuel assets continues to grow sharply. The primary driver of this growth appears to be a continued migration of assets from taxable corporate forms to MLPs, as other possible factors seem to be working in the opposite direction. Lower oil and gas prices and concerns over rising interest rates, for example, have both dampened the rate of increase in MLP share prices. Further, we have seen some very significant MLP-reversals, where MLP assets were "re-corporatized" due to strategic (i.e., non-tax) factors. Foremost here was the merger of Kinder Morgan MLPs back into the parent company, a deal estimated to be worth more than $70 billion. This one transaction alone, absent growth of new MLP assets, would have lopped an equivalent of about 18% of the estimated MLP market cap value when our paper was done (and more than 20% of natural resource-focused MLP portion).

Earth Track and OCI's review of MLPs in mid-2013 found a market cap of all MLPs at about $400 billion, of which about $325 billion was natural resource-related (primarily oil and gas). The National Association of Publicly Traded Partnerships (NAPTP) periodically prepares an industry overview of MLPs called "MLP 101". The last public version of this document in October 2013 estimated market cap of MLPS at $490 billion, of which $422 billion was for natural resource MLPs (see Slide 33) -- again, primarily oil and gas.

Despite the slowdown and the loss of three MLPs related to Kinder Morgan, the MLP sector has continued to grow. Total MLP market capitalization as of May 12, 2015 was $679 billion based on an Earth Track review of listed MLPs. Of this, 77% was associated with fossil fuels -- most heavily oil and gas midstream operations, as has been true in the past as well. Despite this growth in market cap, official estimates by the Joint Committee on Taxation of revenue losses to the US Treasury from the MLP structure holding this growing pool of assets (JCX-97-14, p. 24) have barely changed -- and are flagged at a maximum of $1.2 billion/year through 2018.

Other items of note:

- A handful of renewable energy firms (about $6 billion in market cap) somehow qualified as MLPs and were listed on NAPTPs census.

- There has been robust growth in financially-oriented MLPs as more and more large private equity firms seek to tap less expensive capital via public markets using an MLP share listing. These firms comprised just under 19% of total MLP market cap. Most of these firms have substantial investments in the fossil fuel sector (often through private partnerships that are part of their investment portfolios), though the fossil fuel share of total investments is not known. Many of these firms also have highly compensated executives (some of the wealthiest people in the country, in fact) who are also benefitting from subsidies to carried interests in their funds, taxed at lower capital gains rates rather than standard income tax rates.

- A subset of MLPs have chosen to be taxed as corporations rather than as tax-exempt MLPs. This choice seems rather odd at first, as firms rarely volunteer to be taxed at a higher rate than the minimum required by law. However, further inspection shows that the vast majority of the MLPs choosing this path are in the oil and gas marine transport business, and are often organized outside of the United States. While additional research would be needed to conclusively determine why this is happening, the likely explanation is that these firms are able to access special tax rates, often in tax havens, that generate an even lower effective tax rate (combining the tax hit at both the corporate and and unitholder levels) than would be possible as a pass-through MLP. This is probably a function of the "Alternative Tonnage Tax" that allows tanker firms to choose a (very low) tax on tonnage in lieu of paying corporate income taxes. The law was passed in 2006 in the US, but similar regimes existed for longer in other countries. It provides yet another interesting, though not well-quantified, subsidy to the price of oil we see as consumers.

3) Expansion of tax-exempt corporate structure to renewable assets via REIT and YieldCo structures. As noted above, energy assets have been shedding corporate tax liability via at least three main venues: MLPs, energy-related REITs, and YieldCos.

Two years ago, federal legislation to expand MLP eligibility was being pushed heavily (primarily by Senator Christopher Coons of Delaware). My concern was that the legislation would (a) make it impossible to ever kill tax-subsidies to oil and gas MLPs (indeed, oil state reps like Lisa Murkowski seemed to recognize this angle, and were co-sponsors of the Coons bill); and (b) open the tax exemption to a larger set of energy assets than perhaps had been intended. This seemed likely to include power generation and transmission of all types. Yet, when the revenue loss of the Coons bill was scored by the US Joint Committee on taxation, they estimated an average of only $130 million/year over the ten year period of estimates. Details behind their calculations were not made public, so it was not possible to evaluate their scoping or assumptions. But the figure still seems very low to me.

The successful roll-out of YieldCos may render MLP expansion moot. In but a handful of years, YieldCos have gone from a theoretical construct to a growing number of firms and tax-favored assets. With a current market cap of more than $25 billion, the sector is on-track to hit $100 billion within a few years according to Jeff McDermott of Greentech Capital Advisors. A YieldCo-specific ETF has just been launched as well.

A review of the corporate structure of YieldCos versus MLPs suggests that they have attributes that make them easier to invest in for some institutional investors (emphasis added):

Several factors differentiate a YieldCo from a MLP - including a more traditional tax treatment, which makes it easier to invest in for many institutional investors. First, a YieldCo is a corporation, not a partnership or limited liability corporation like a MLP. Second, assets often targeted for a YieldCo - such as renewable and contracted

conventional plants - are not "MLP-able" under current law. Third, YieldCo's are not eligible for pass through tax treatment, although often maintain significant tax shields and NOLs that mitigate cash tax outflows.[fn]Source: Goldman Sachs Equity Research, "Juncture to Restructure: YieldCo 101," May 14, 2014.[/fn]

It is notable that my concern about tax-favored status to conventional power plants emerging from MLP-expansion may actually materialize via the YieldCo structure instead.

What of the energy-related REITs? Drop-downs of power transmission assets into tax-exempt REIT structures have begun, facilitated by the 2014 IRS ruling. InfraReit, for example (ticker HIFR), holds a chunk of TX assets owned by the Hunt family (the nation's 13th wealthiest family according to Forbes) in a new, corporate framework exempt from corporate-level taxation.

No, the Hunt family is not doing anything illegal: they are simply leveraging existing law to their benefit. But the policy trade-offs, and who benefits, are worth thinking about. And the migration of transmission assets off of corporate tax roles is likely to accelerate -- a trend, by the way, that is most likely to help large scale, centralized conventional power generators while disadvantaging smaller scale distributed generators and energy efficiency.

Energy-related REIT assets are a fast-growing share of the "non-traditional" REIT universe, according to data from SNL Financial gathered by Ernst & Young (page 15). The Edison Electric Institute notes (page 6) transmission investments running more than $10 billion per year from 2011 forward by private utilities, so the scale of assets moving off of the tax roles via "WireREITs" could be as significant as we've already seen with MLPs and non-energy REITs.

The effort to push ever more low-cost capital into energy infrastructure of all types is happening in somewhat of a vacuum. Lawmakers and lobbyists alike are ignoring the distortionary impact that these tax-exempt corporate forms for "special" industries have on the equality of business opportunity within the country. We should not be.

But it is because of this long involvement that I can see the many ways in which the current work moves the ball on subsidy transparency and reform. Here are some of them:

But it is because of this long involvement that I can see the many ways in which the current work moves the ball on subsidy transparency and reform. Here are some of them:

ill hopefully have time to do a more detailed discussion of the paper in the near future. For the time being, however, it is useful to keep in mind that the IMF's numbers are much larger than other estimates (for example, by the OECD, IEA, and World Bank) primarily because of their incorporation of negative externalities (environmental as well as those related to traffic) and their imputation of baseline taxes on fuels if current levels are too low or non-existent (such as a national sales tax on motor fuels in the US).

ill hopefully have time to do a more detailed discussion of the paper in the near future. For the time being, however, it is useful to keep in mind that the IMF's numbers are much larger than other estimates (for example, by the OECD, IEA, and World Bank) primarily because of their incorporation of negative externalities (environmental as well as those related to traffic) and their imputation of baseline taxes on fuels if current levels are too low or non-existent (such as a national sales tax on motor fuels in the US).

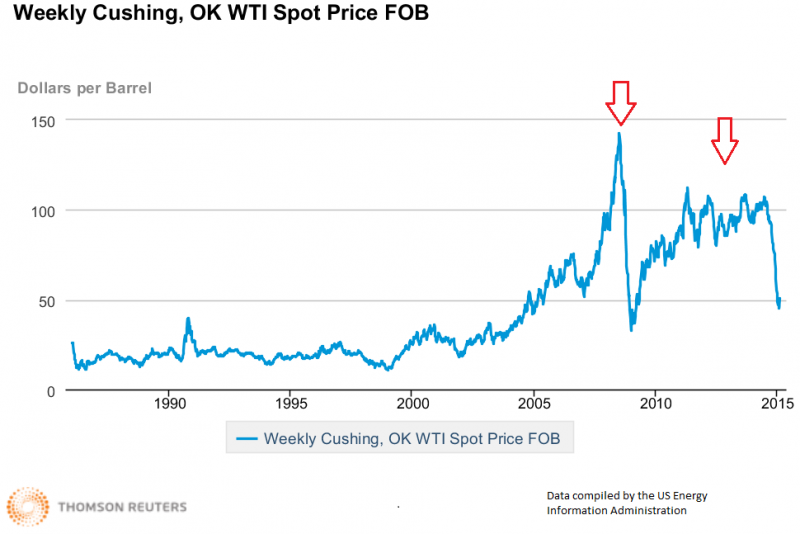

imal time to have rid ones statutes of producer subsidies was during the fat years (see graphic) when fuel prices were surging: 2007-08 (before the credit collapse), or again the past few years when prices for fuels were again quite high.

imal time to have rid ones statutes of producer subsidies was during the fat years (see graphic) when fuel prices were surging: 2007-08 (before the credit collapse), or again the past few years when prices for fuels were again quite high.